Cold War networks of literary translations

part 3 of a series about Second World Literature

Cold War culture now seems remarkable for how both political-military blocs were promoting literacy and literature, including world literature, as a bulwark against the barbarity of the other. Come to think of it—it was a bit like the space race: each side claiming to be the true representative of human progress and universal human values, notions articulated in similar although not identical terms. In two previous posts (here is the first, and here is the second), we started to describe Second World Literature, i.e., the world literature of the Second World. We are interested in the world-literary landscape of the Soviet bloc: how it differed from its First World counterpart, what works were circulating in translation, and what were the paths, the patterns, and the mechanisms of circulation.

Recap and background

We are analyzing the bibliography of all published translations of Hungarian literary works in any language. We look at what got translated, in what chronological order, into what languages and in what countries, identifying translation flows within the Eastern Bloc itself as well as between East and West. Our data provides a partial view of the Cold War system of world literature. Obviously, not all literature circulating within the Second World was originally written there. The trajectories of Hungarian books in translation are not necessarily fully representative of the circulation of all that was produced on the eastern side of the Iron Curtain, either. We are working on getting more data to look at the landscape from other perspectives as well. But as we suggested before, we see translation flows forming a giant global network, and the dataset we have been working with already allows us to track these flows—much like throwing a stick into a turbulent river allows you to see the direction of the current. Other datasets will work as sticks thrown from different points along the banks of the river. The more sticks we throw, the better map we can draw. We will post here about new datasets and the insights gained from them, but there is plenty more to squeeze from the one we already have.

We have shown that the Second World of literature was neither monolithic, nor were all translation flows directed by the Russian center. Rather, the Second World itself was divided into two halves—the Republics of the Soviet Union, and the Eastern-European countries that came under Soviet control after WW2. Russian publishing functioned as a bridge between the two. While Russian clearly controlled the flow of translations to the languages of the other Soviet republics, what was chosen to be translated into Russian mostly followed rather than lead the choices made in other Eastern European.

The difference between the two halves really became marked after 1956. During the Stalinist period, up until 1956, the regime of translations—like everything else—was thoroughly centralized and Sovietized throughout the Eastern Bloc. In Hungary, a chain of Russian-language bookshops was also established, with stores in major towns, including several in Budapest. (To clarify: not instead, but alongside bookstores selling Hungarian publications.) Not everyone was enthusiastic about their offerings. In October 1956, during the uprising against Soviet rule, crowds threw the contents of those stores into the streets and set the books on fire.

1956 was also the year of the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the USSR and of uprisings and political upheaval in Poland. It was a watershed in the history of the Second World, the end of Stalinism in Eastern Europe. It brought a glimmer of cultural independence, which in turn lead to the growing difference between the literary landscapes of eastern Europe and the Soviet republics.

What does our data suggest about literary communication between this internally differentiated Eastern Bloc and the First World? In analyzing the patterns of translation of Hungarian works, we are taking the same approach as before: we look at the chronological order in which various regions (linguistic-political entities) translated Hungarian authors. (For a more fine-grained analysis, we are also planning to perform the same analysis for individual works.)

A closer look at the network

(Here follows prose… scroll down to the end for the main insights of the analysis.)

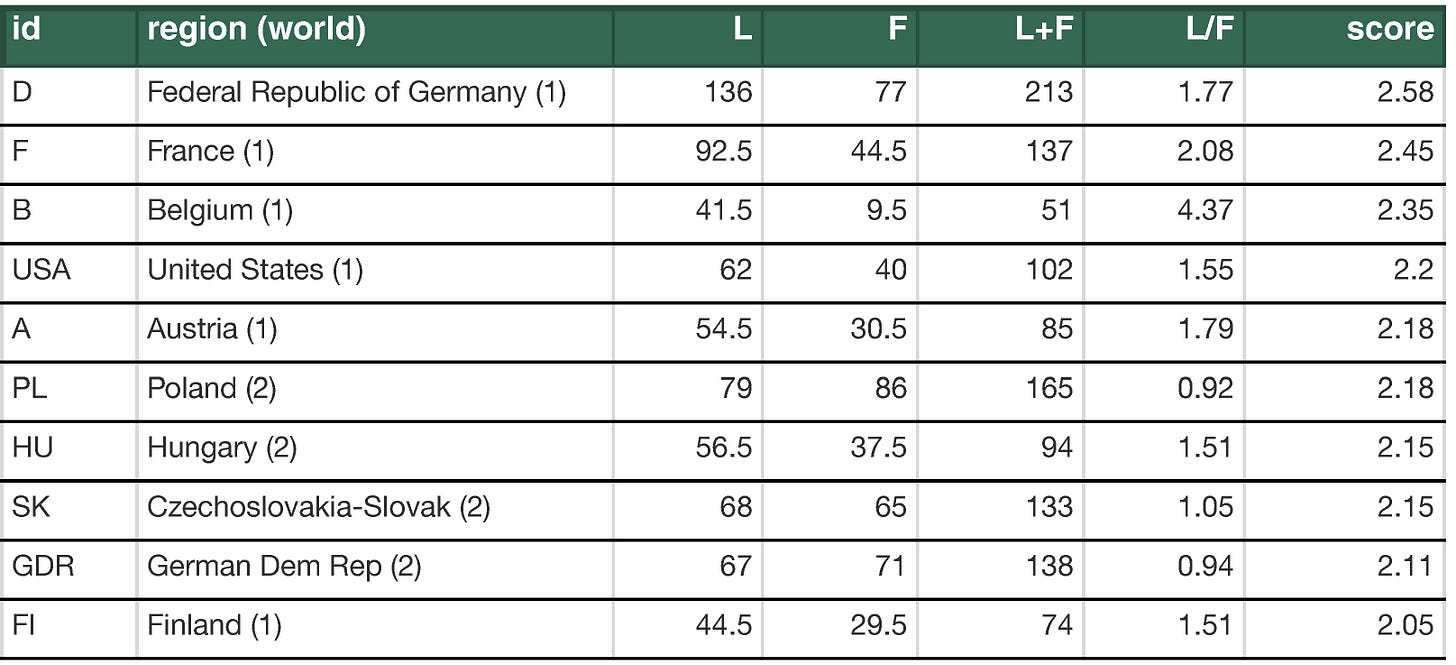

After establishing the chronological sequence in which individual authors were translated into various languages, we ranked regions (languages as political units, as we explained in a previous post) according to their positions in the totality of these authorial sequences, calculating a the Translation Lead Score (TLS) for each region.

We used the simple formula log10((L+F)*(L/F)) to calculate the TLS for each region, where L is the total number of times the region leads or precedes another region in translating an author, and F the number of times it follows another region. L is the sum of the number of authors each region published before another node, so if an author is published in Poland before it would also have been published in France, Czech, Romania, Bulgaria, it adds 4 to the value of L. And if an author was published in Poland after it had been published in West Germany and Ukraine, then it adds 2 to the value of F.

The formula reflects 1., the sum of the weight of all the edges connecting a region to all other regions, regardless of the direction, where the weight of each edge is the number of authors shared with another region, in brief: the sheer number of shared authors, and 2., the ratio of the number of times the region preceded vs. followed another region in publishing an author—higher than 1 if the region leads more often than it follows, and lower than 1 if it follows more often than it leads. To arrive at a more manageable score, we take the common logarithm of the product of these two values.

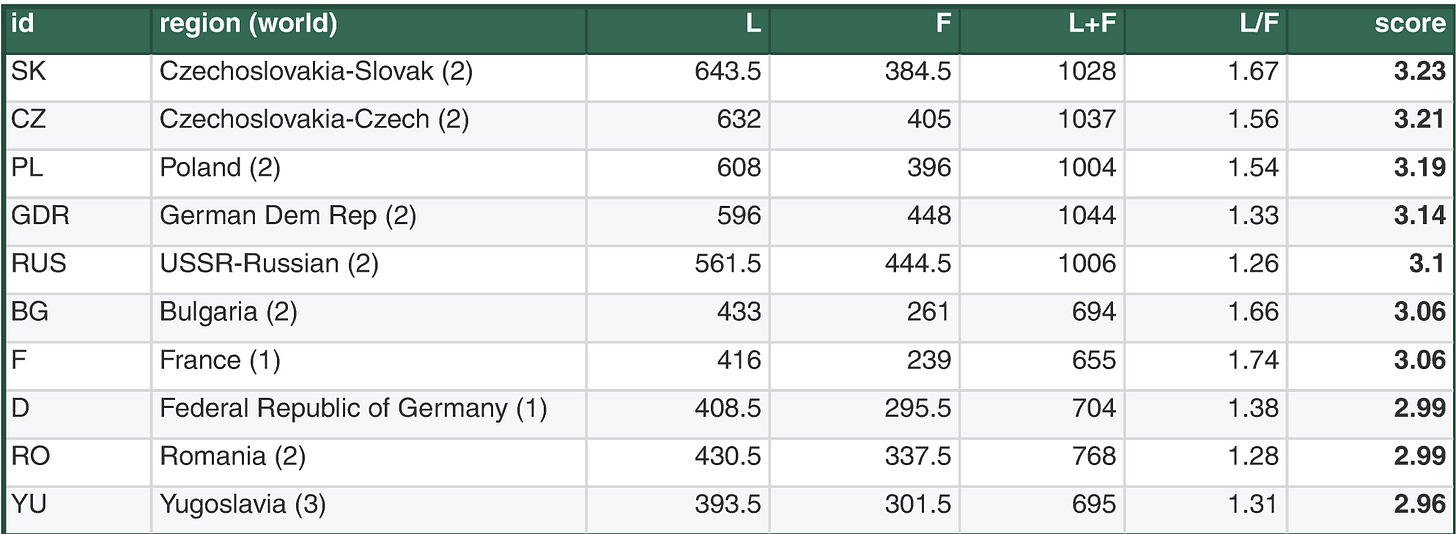

Here are the ten regions with the highest TLS:

Note that France has a higher L/F ratio than any other region in this top ten list: its relatively low TLS is due to the lower total weight of the edges, in other words, to the lower number of authors it shares with other regions. Fewer authors were published in French than in some other languages—but when an author was translated into French, that preceded rather than followed translations into other languages. Again, put differently: an author translated into French had a better chance of then being translated into other languages than an author published in translation in any other region in this top ten. Of the ten, Russian has the lowest L/F ratio: once again, it is the the sheer number of shared authors that affords Russia a higher TLS.

So far, we have been looking at the network of all Hungarian authors translated into any foreign language (or rather, into at least 2 foreign languages: since authors are the edges of the network, an author who was only translated into one language does not figure in the network). Let’s now filter out authors who were published in the First World.

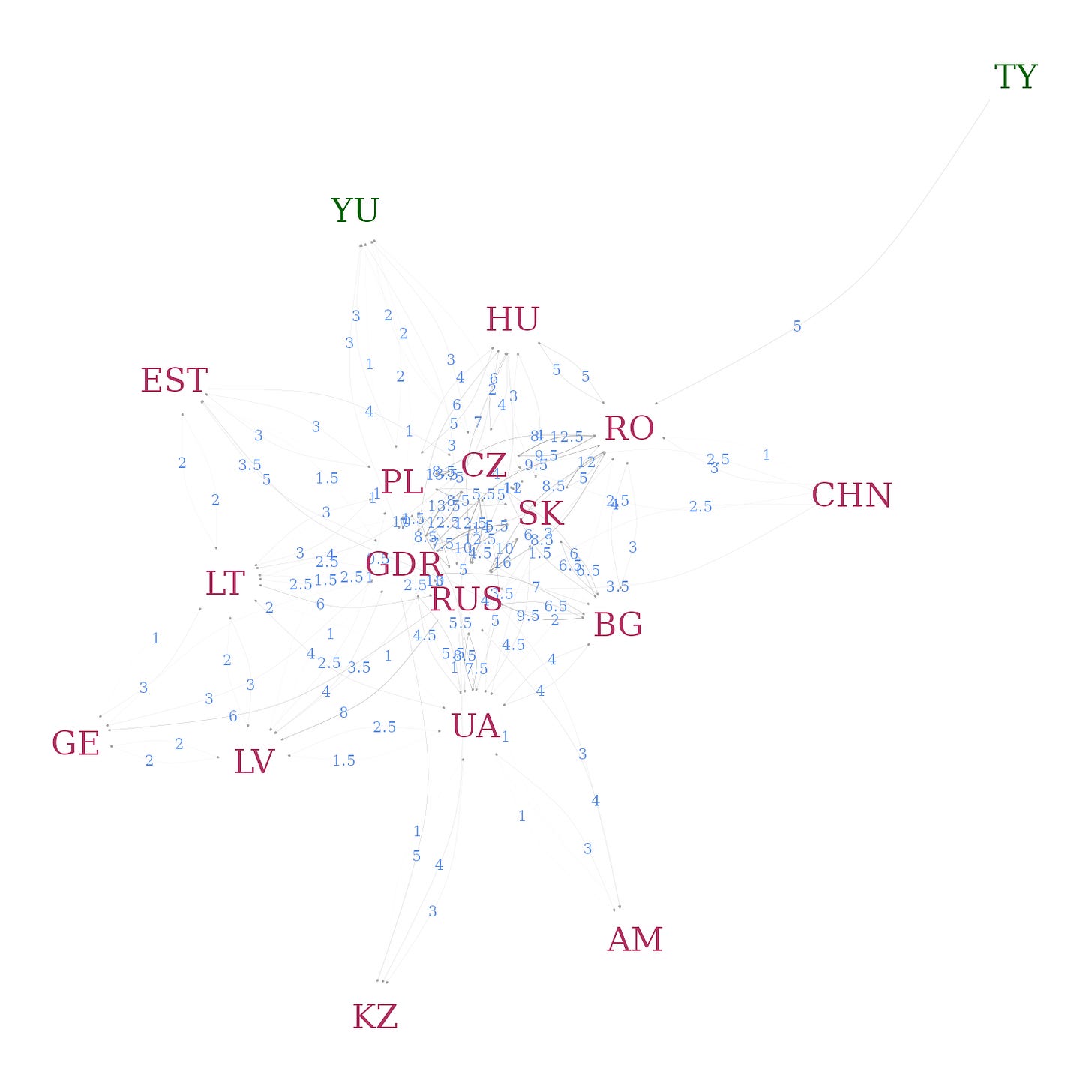

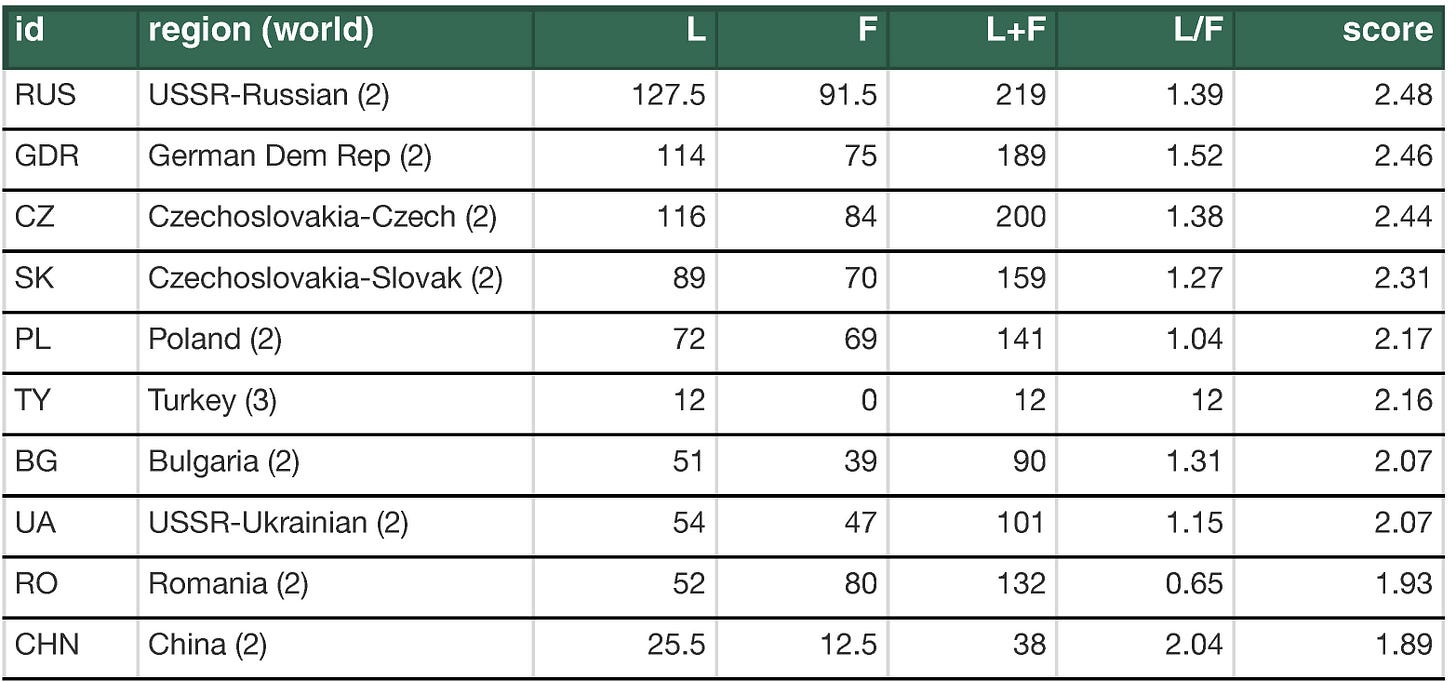

This is the network of authors not published in any First World country—for better visibility, the threshold is set at four, i.e. only edges with a weight no smaller than 4 are shown. In this network, Russian is still between Eastern Europe and the Soviet Republics. But it is not a relative follower. Here are the Translation Lead Scores calculated for this set of authors:

The combined effect of the total weight of edges connecting it to other regions, and the ratio of leading / following relations, is that Russian has the highest score when it comes to authors not published in the First World. When it comes to authors never published in the West, Russian has relative dominance. Only relative though: even when considering just this set of authors, we cannot really talk about the absolute centrality of any region.

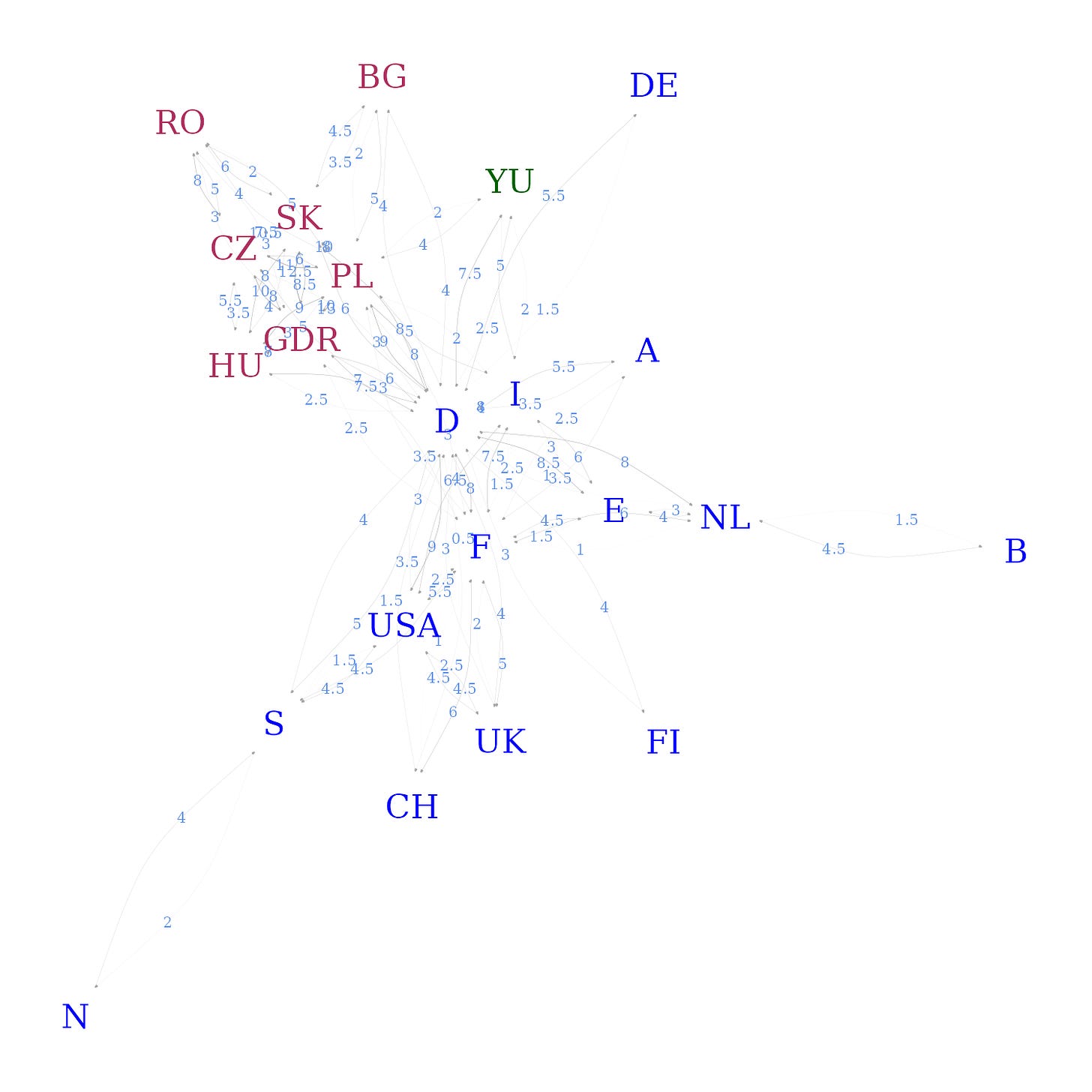

If we take the opposite selection, i.e. the network created by authors not translated in the Soviet Union (and setting the threshold for the visualization at 6, i.e. no edges show whose weight is less than 6) this is what we get:

This network is centered on West Germany (and the weight of 1st World German translations would be even more striking if we combined FDR imprints with Austrian and Swiss publications). The Eastern-European countries still form a tightly knit group, with Romania and Bulgaria slightly peripheral. And here are the regions with the top ten TLS for this network:

Here, the ranking reflects a more complex situation than in the earlier tables. The centrality of West Germany to this network coincides with its tendency to translate authors before others. Some of this is simply a function of the high number of Hungarian authors published there: of all regions in this part of the network, Germany has edges with the highest total weight. France’s TLS is close second due to its high relative priority (high L/F value) within this network (as well as in the network as a whole, as we saw earlier). In the Cold War period, French translations had a high chance of being trendsetters, especially in the First World: higher than translations published in West Germany, in spite of the higher volume of publications in German.

The appearance of Belgium in this top list is interesting. We could split Belgian publications according to language, and grouping them with French or Dutch. The strikingly high L number, and correspondingly high L/F value is due less to the uncanny ability of Belgian publishers to direct or at least anticipate translations flows, and more to a handful of émigré writers whose work first appeared there, and was later also published in France or the Netherlands. Belgium does not appear in the first table because when it came to authors also published in the Soviet Union (which included national classics), Belgian publications were clearly followers, not leaders.

The relatively high ranking of Hungary on this list speaks to the modest success of the foreign language Budapest-based publishing house Corvina in publishing translations of Hungarian authors who were then also published elsewhere.

Other eastern European countries are present because of the large number of authors they shared with other regions, but in this network, they are followers rather than leaders—which implies that their edge in the total network was due to their translations to precede rather than follow the first Soviet translation of an author.

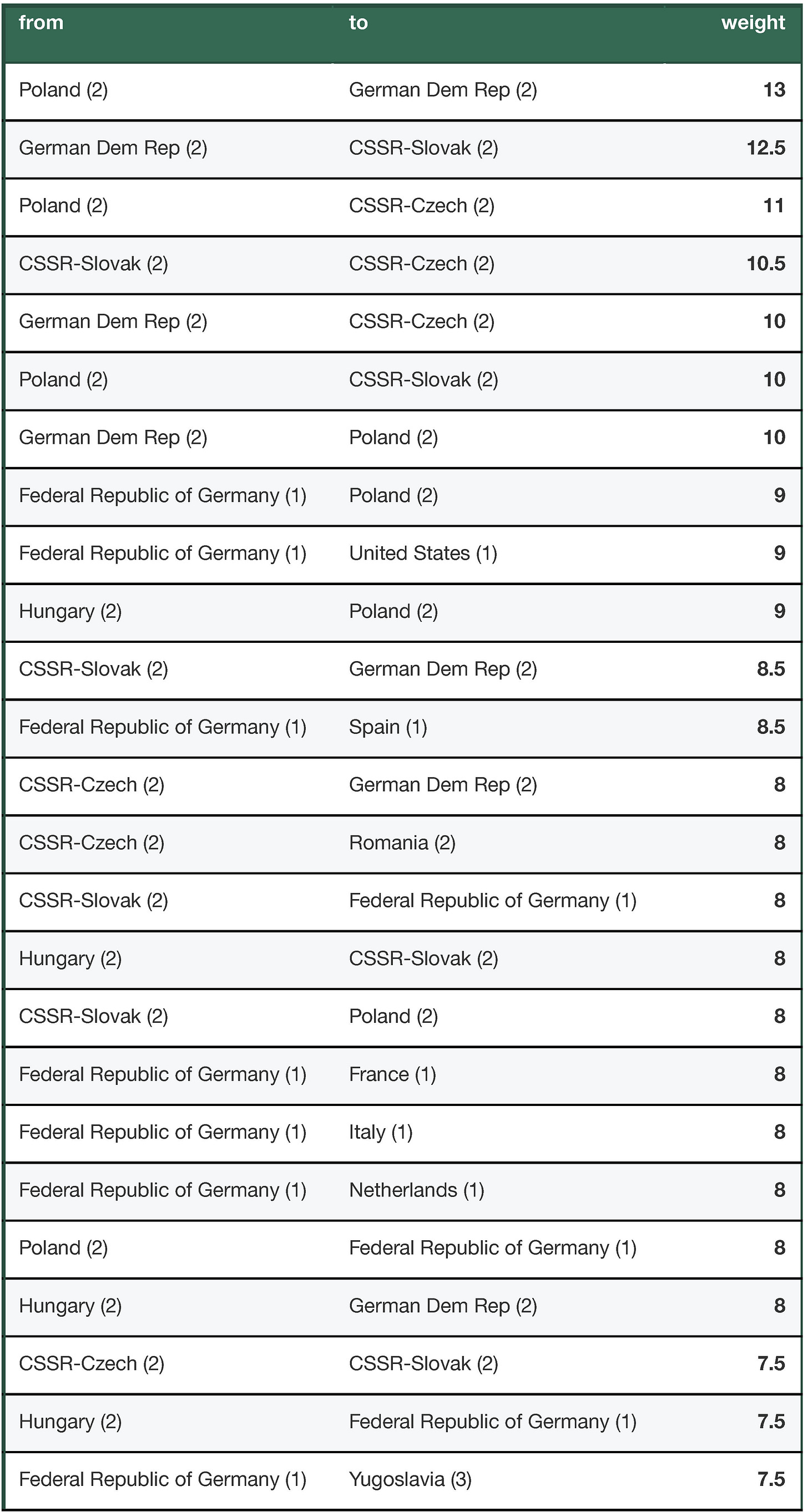

If we glance at the table of the weight of the outgoing edges that connect one node to another, we see how the large number of authors published in the Eastern Bloc shapes this network (we are still looking only at the network authors who were not published in the Soviet Union during our period):

A lot of Hungarian authors were published in Second World countries, and if an author appeared in one Eastern European language, it often appeared in several others as well. What the TLS numbers in Table 3 above reveal is how in the broader network, which also includes countries/languages with a small number of translations from Hungarian, the most important points of orientation were the First World centers of France, the Federal Republic, and the USA. If we look at Table 4, a list of the 25 directed edges with the highest number of authors, we see that the 1st and 3rd world countries all make their first appearance on edges coming from the Federal Republic: the US, Spain, France, Italy, the Netherlands each translate more Hungarian authors after they were published in West Germany than after any other region. West Germany itself shares a lot with, and tends to follow some Eastern Bloc countries—but the Federal Republic’s role as the largest node with edges leading to other first world regions means that those other countries were likely orienting themselves after the editorial choices made by German publishers.

So what’s the payoff of this analysis?

Based on the circulation of Hungarian writing, it seems that the literature of the Eastern Bloc was mediated to the First World by West Germany, and (following a different pattern: fewer titles, but more global traction) by France.

Among Second World regions, Poland, Slovakia, and the German Democratic Republic published the highest number of authors before those would have been published in the First World—but in spite of those high numbers and their relative centrality to the network, they do not direct the flow towards the West; publications in other, smaller First World regions have more overlaps with the West German and the French output than with any Second World region, even though those two Western regions publish fewer authors than any of the Eastern-European regions. (To show this more clearly, an additional image and table of the network of authors who were published in the First World would be needed.)

Obviously, a high TLS only means post hoc, not propter hoc: chronology is not causality. If (in the part of network created by authors not published in the Soviet Union) translations in West Germany and France more often precede than follow translations into Eastern European regions, that does not automatically mean that Eastern European publishing was following the lead of those Western translations. But it is quite probable, and in some anecdotal cases a known fact, that translations published in France and West Germany did call the attention of Polish or Czech or East German publishers to Hungarian titles, thus prompting translation in Eastern Europe. In the post-Stalinist period, the bilateral Second World arrangements were inflected by an awareness of the cultural marketplace of the First World.

Next: about the writing underlying all this.