3 percent, 60 percent: the singularity of English in the world of translations

making sense of some crude numbers

Our project is not about translations from or into English, the centrality of English to global translation flows, or what percentage of American books are translations.

But English being the dominant language of world literature now, we obviously think about these issues. They are also very relevant to one of our interests, namely, to whether and how the publication of literary translations constitute a world system. So here is how we understand the publication of literary translations into English and from English at the turn of the millennium, based on the existing quantitative research on the macro scale that allows us to make sense of “the 3%.”

The 3% problem

It is a widely reported fact that among English-language publications, the share of translations is surprisingly low. The figure usually mentioned is 3%—in most other “major” languages, the share of translations seems to be in the low double digits, and in many “small” languages their percentage of all publications is even higher.

As Lawrence Venuti put it, these “translation patterns point to a trade imbalance with serious cultural ramifications.”1 The likely effects of the lack of (cultural, intellectual, literary) diversity Anglophone readers are exposed to are obvious. Living in a culture where 30% of the contents of a bookstore are translations is very different from living in a culture where only 3% of the books are. No matter how proportionate or disproportionate this may be—and disproportionate to what exactly—familiarity with other literary cultures, even if only in translation, makes a difference to one’s experience of the world.

3% became a meme after a 1999 National Endowment for the Arts report, and a 2005 news release by Bowker, publisher of Books in Print and information provider to the book publishing industry. This is how Bowker summarized their data about translations:

The English-speaking countries remain relatively inhospitable to translations into English from other languages. In all, there were only 14,440 new translations in 2004, accounting for a little more than 3% of all books available for sale.2

At the time the 3% figure made headlines (at least in the smallish world that cares about these things), American literary culture was arguably quite solipsistic, but the very fact of worrying about the number was a sign of change. For example, Chad Post cannot be praised enough for maintaining an influential blog named 3%, intended to call attention to and also help remedy the problem, and for creating a database to make it possible to actually have a sense of how much—and what—gets translated.

Due to such and similar efforts—new presses dedicated to publishing literature in translation, independent bookstores that sell them, online publications that discuss them—the situation seems to have improved in recent years, both in terms of the cultural visibility of translations and in terms of the sheer number of new translations being published. In 2018, the Washington Post ran a piece by Liesl Schillinger with the title “The Surge in Literary Translations since 9/11” on the front page of its Sunday cultural section, which pointed out that the number of literary titles in translation in 2018 was 600, twice as many as in 1999, and this growth also outpaced the overall expansion of the bookmarket, so the share of translations increased from 3% to a jaw-dropping 4%.3 But there is a widespread sense that translations still don’t get the attention from mainstream American (and British?) literary culture that they deserve. And there is evidence to point to: the NYT 100 notable books of 2024 only include 4 translations.4 So maybe 4% is the new 3%.

How low is 3% and why isn’t it higher?

How low the 3% really is, is a question of comparison. We can try and make sense of the share of translations from the total number of publications in a country or a language not only as a symptom of a culture’s narcissism or insularity (or conversely of its openness or cosmopolitan virtues), but also from the perspective of global translation flows, of the quantitative logic of circulation. Here, another widely reported number might be helpful: perhaps 60% of all translated books published worldwide are now translated from English—all other source languages share the remaining, and ever shrinking, other half. Not only that: well over 20% of all titles published worldwide are actually in English.5

We will write a separate post about the decades-old data on which this is based, and about the lack of current, accessible data. For now, some thoughts based on the numbers we have.

The sheer volume of production in English, and the dominance of English as a source language, are arguably a reason why only such a small percentage of English-language books are translations. This is among the suggestions by Alexandra Büchler and Giulia Trentacosti (Literature Across Frontiers), in the most recent sustained effort to look at the 3% problem that we are aware of.6 According to the information they gathered, in 2011, of all titles published in the UK and Ireland, 3.16% were translations, and while the absolute number of books published continued to grow, the share of translations still hovered around the 3% mark in 2015.7

In 2011, the share of translations in Germany was 12.28 %, and in France, 15.9%. But the majority of those translations into German and French were from English: 63% of all translations in Germany and 61.8% in France were translations of texts originally written in English. This skews statistical comparisons: if you exclude translations from English, the share of the remaining translated books of all publications, 4.54% in Germany, 6.07% in France, resembles the low figure seen in English-speaking countries more closely.8

Still, the figures for the UK + Ireland show an obvious deficit when compared to the number of translations published in other European countries. In terms of absolute numbers, even after excluding translations from English, there were ca. 3200 translated titles published in Germany and ca. 4900 in France—compared to a total of 2770 titles translated from any language in the UK + Ireland. In practical terms, the chances of finding a translation of a particular book written in any language other than English are definitely higher in Germany or France than in the UK + Ireland. The comparison with other national book markets might have even harsher results. Poland and Italy both publish a lot of translations. The Literature Across Frontiers (LAF) report only indicates the breakdown according to source languages for France and Germany, but if those figures can serve as guidance (and they are pretty close to what we can see globally)9 then the number of Polish books that are translations from any language other than English is probably close to the German number, while the Italian number exceeds even the French output.

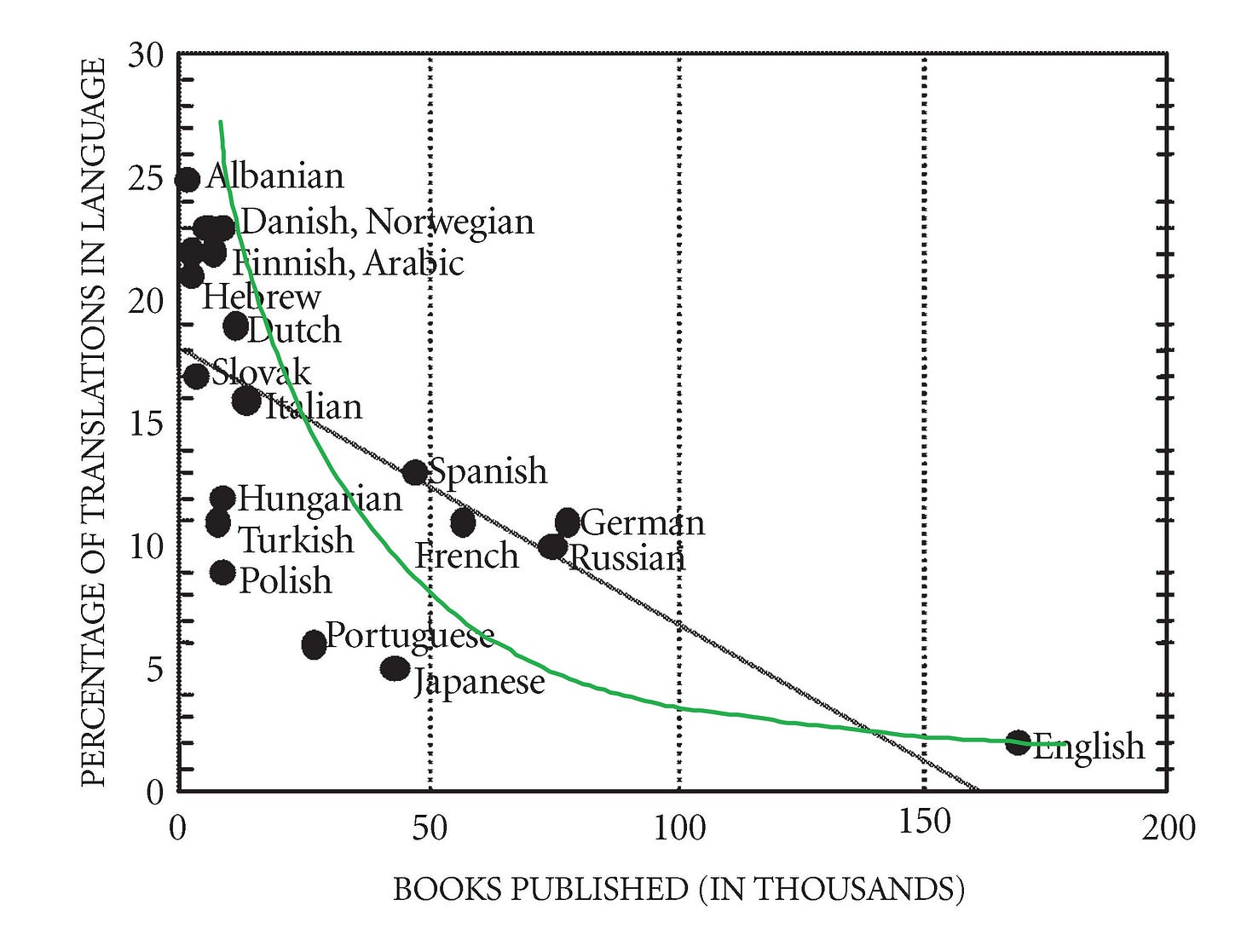

The LAF reports are mostly descriptive of their data, their generalizations convey common-sense impressions. Among the very few pieces we have found that actually tried to discern the logic underlying the statistics is a 2005 essay by Anthony Pym and Grzegorz Chrupała. Working with the global data from UNESCO, they looked at the relationship between translation percentages and the size of the publishing systems concerned, and show the correlation between the number of publications in a target language and the percentage of translations in that language.10 They illustrated their findings with the following graph:

Pym and Chrupała used a diagonal to indicate the overall tendency, but their article suggests that an algebraic curve would better fit the distribution of the data points—so we sketched one in. The point is: a regression analysis of the available data seems to suggest that in this translation universe, the tendency for the percentage of translations is to decrease with the number of publications in that language. (More precisely: the percentage of translations decreases with the increase in the share of the language of total world-wide publications.) Given the high number of English language publications, a low percentage of translations into English is to be expected. The disappointing volume and low visibility of translation into English correlate with the global dominance of English language publishing, and might be seen as its effect.

In a later publication, Pym argued that their analysis showed that

the bigger the publication space of the target language, the lower the percentage of translations in that language (so the low percentage of translations in the United States could be due to the high number of books published, rather than a direct consequence of cultural hegemony). In fact, the purpose of the exercise was to question the common assumption that the relatively low percentages of translations into English are a direct indicator of hegemony (cf. Venuti 1995).11

But Pym and Chrupała’s 2005 analysis does nothing of the sort. Such analysis obviously does not and cannot speak to the question of the actual mechanisms that result in these outcomes. What the graph does suggest is that those mechanisms do not seem to operate differently in the case of English than with other languages. Contrary to Pym’s 2009 claim, it actually shows that—if cultural hegemony is quantified as the share of English in the global book market—the low percentage of translations can be thought of as an indicator (a function) of the hegemony of English in the global production and circulation of books.12

The huge global uptake, the business of the sales of translation rights of English-language works, both fuels original production and de-incentivizes translation. Once you dominate production, your market position makes you lose interest in translation. This is why non-profits and university presses are driving the expansion of the publishing of translations into English, counteracting the statistical tendency: they have motives other than strictly commercial.

If anything, Pym and Chrupała’s analysis supports as well as complements rather than questions Venuti’s suggestion that

British and American publishers … have reaped the financial benefits of successfully imposing English language cultural values on a vast foreign readership, while producing cultures in the United Kingdom and the United States that are aggressively monolingual, unreceptive to foreign literatures, accustomed to fluent translations that invisibly inscribe foreign texts with British and American values and provide readers with the narcissistic experience of recognizing their own culture in a cultural other.13

It is true that Venuti’s language might seem to imply ideological agency and imperial ambition, but if we bracket the imputed intentionality, and see publishers “successfully imposing …values” and “producing cultures” not as the fulfillment of their infernal goals, but as the real, political effects of commercial activities (and of scale), the two approaches can in fact speak to one another.

Neither Venuti’s nor Pym’s arguments suggest that cultural policies, funding, and other, idealistic, even utopian efforts could not meaningfully increase the share of translations.

What seems pretty clear is that commercial circulation left to its own devices won’t do it.

Systems revealed by the data

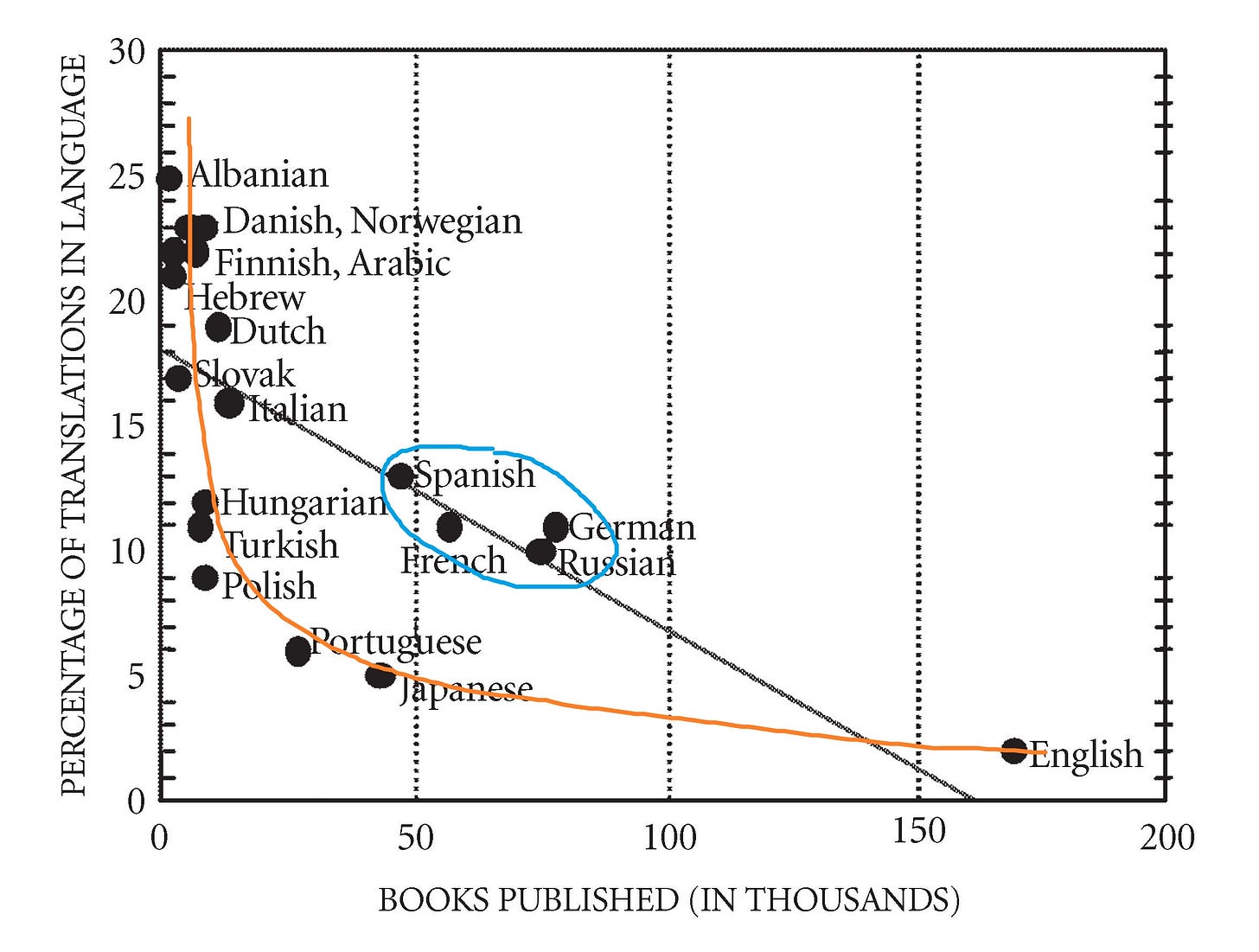

Let’s take another look at Pym and Chrupała’s graph. In their essay, they point out that there is an interesting group here—Russian, French, Spanish, and German—that have a higher percentage of translations than what one would expect based on the curve:

If all we can say that these four are outliers, then the whole account is not very useful. Pym and Chrupała see here “quite different behaviour for a group of small languages, for a group of large national languages, and for English out there all by itself,” suggesting “there may be groups of languages obeying quite different dynamics, such that further analysis would have to consider each group on its own terms.”14 We should add: this analysis needs to be done without losing sight of the system as a whole.

There is a framework that does that: describes a system that distinguishes among these language groups—but without giving up on seeing them in their interconnectedness, each case being determined by all the other languages participating in the global circulation of translations. It was sketched out by people in the field of the sociology of translation, who applied a crude version of world systems analysis to translation flows, tracing a historically evolving, hierarchical world system of translations. The model distinguishes between centers and peripheries: not as terms of praise and condescension, but as positions in the web of circulation. In the world system of unequal flows, translations primarily flow from centers towards peripheries—or rather, centers are defined as places from where translations flow to the periphery. In the last third of the 20th century, the period these studies focused on, the world system consisted of a lot of peripheral and semi-peripheral languages, a handful of central languages, and the super-central language of English.

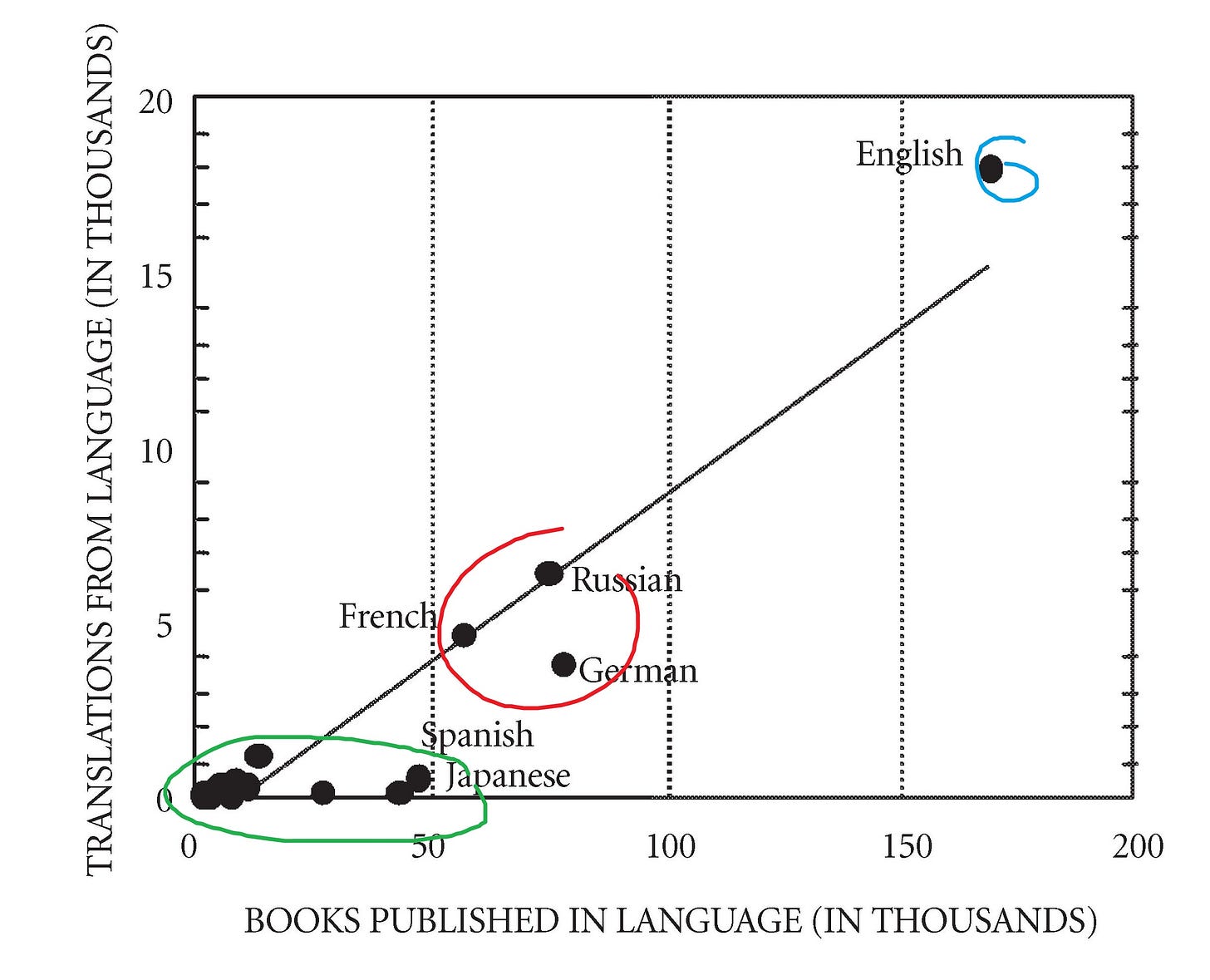

The seminal study in this field is a 1999 essay by Johan Heilbron.15 He and others in his wake identified two distinct characteristics that describe the centrality or marginality of languages in the world system of translations. The first is their status as source languages. This serves as the definition of centrality in Heilbron, who says that the larger the share of a source language in translations published worldwide, the more central in the world-system of translation it is. There is a graph in Pym and Chrupała 2005 that can illustrate the degrees of centrality in these terms, even though their own discussion of it is hardly satisfactory:

Pym and Chrupała argue that the number of translations from a language is a function of the total number of books published in a language. But a look at their chart makes one wonder about that—about the difference between Spanish and Japanese on the one hand, and French on the other. Not to mention Chinese, for which they do not have data—an enormous publishing industry with very little traction in translation. We will need to come back to the question of how this system of inequalities emerges and how it changes.

Other than being dominant as sources, central languages typically also govern or direct translation flows between other centers as well as between peripheries: peripheries communicate via the centers. Translation into a central language tends to pave the way for, and even prompt translation into peripheral languages—in other words, central languages serve as gateways for translations into other languages. Central languages have played this role among vernaculars for the past quarter of a millennium, from the French-centered system of the 18th century through the 21st-century English-centered system. In the past, this gateway function often meant that it were translations into a central language that were then re-translated into other peripheral languages. Such re-translation is now less common, but being translated into French, German, or English does certainly make a title from a peripheral language visible to potential publishers.

Heilbron argued that

the more central a language is in the translation system, the more it has the capacity to function as an intermediary or vehicular language, that is as a means of communication between language groups which are themselves peripheral or semi-peripheral. (435)

There clearly seems to be a co-incidence of the two features, but unlike the absolute of relative quantity of translations, the actual role of a language as a gateway or intermediary is very hard to quantify. Heilbron’s formulation is rather canny: he talks about the “capacity to function as an intermediary or vehicular language,” not about the extent to which this is in fact happening.

One relevant metric might be the volume of translations into a language. Its significance as a source language establishes the attention paid to it, but it is the translations for which it is the target language that do the work of mediation. And here, the low relative volume of translations into English (the 3% problem), as well as the low internal prestige of those translations might suggest that the supercentral English is less important as a gateway language than one might expect. The brunt of that work of mediation is done by central languages, primarily, by French and German. Of course, the translation of a peripheral text into English is significant, and may also have a certain multiplying effect: but the importance of English as a gateway may not be proportionate to its brutal super-centrality as source language.

There has been a fair amount of work on these issues by scholars working within a world system theory / sociology of translation framework. We chose to only engage with a few publications in developing what is an absolutely skeletal and macroscopic account.16

To understand how the system actually operates, how the centers control its flows, what agents and what channels populate and operate it, what factors influence its dynamics, is something that requires a closer look and tools less blunt than the crude statistics we were citing here.

So there will be posts about what looking at the system of circulation from the perspective of peripheral languages might reveal.

There is also a lot of fudging of specifics above, slippages between “language” and “country,” vagueness about dates, lack of clarity about what these numbers express. So we will also write about the problem of the data: what information we have, how it can be used, and how we could have more, and more recent information.

Lawrence Venuti: The translator’s invisibility: a history of translation. Third edition (first ed. 1995). New York: Routledge, [2018], p. 12.

“English-Speaking Countries Published 375,000 New Books Worldwide in 2004. Global Books In Print Database Reports Fiction Titles Up Last Year, But Computer Titles Plummeted.” New Providence, N.J., October 12, 2005. The original link to the news release, http://www.bowker.com/press/bowker/2005_1012_bowker.htm, is dead. Here is a link to a capture at Wayback machine.

The Washington Post, Sunday, November 25, 2018, B1.

The 100 most important books of the century, published in the NYT earlier this year, looks a bit better: it has 13 translations, by 10 authors. But when they asked the readers to vote, that second list only included 6 translations.

See Sergey Lobachev’s overview of UNESCO publication data: “Top languages in global information production” Partnership: The Canadian Journal of Library and Information Practice and Research 3:2 (Dec. 2008), doi:10.21083/partnership.v3i2.826.

See Alexandra Büchler and Giulia Trentacosti, Publishing translated literature in the United Kingdom and Ireland 1990 - 2012: statistical report. Literature across Frontiers, 2015. The data in this paragraph and the next are taken from this study. The focus of this study are translations into English published in the UK and Ireland.

A statistical update in 2017 brings the UK + Ireland data up to 2015, but does not include information about other countries. See Giulia Trentacosti and Jennifer Nicholls, Publishing Translated Literature in the United Kingdom and Ireland 1990 - 2015: Statistical Report Update. Literature across Frontiers, 2017.

Of course, this is not the full picture: given that maybe a third of all books translated into English are from French, for example, we should do a comparison where English, German, and French are all excluded from all three, and compare what percentage of the books are translations from the rest of the world. Which would result in a differently skewed picture…

For global figures, see the statistics in Publishing Translations in Europe: Trends 1990-2005, Based on analysis of the Index Translationum database. Prepared by Budapest Observatory. Literature across Frontiers, 2011. (The Budapest Observatory is a perfectly obscure entity

Anthony Pym and Grzegorz Chrupała, “The quantitative analysis of translation flows in the age of an international language,” in L M West and A Branchadell (eds.), Less Translated Languages (John Benjamins, 2005), 27-38.

Sandra Poupaud, Anthony Pym and Ester Torres Simón: “Finding Translations. On the Use of Bibliographical Databases in Translation History” Meta: Journal des traducteurs / Translators' Journal 54:2 (juin 2009) 264-278, DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/037680ar.

What Pym and Chrupała’s 2005 analysis does, is question a naive and voluntaristic understanding of cultural domination and its effects. That the percentage of translations are predictably reflective of the volume of book production, and that English fits the statistical tendency, means that the low percentage of translations among English books cannot simply be blamed on particular, individual intentions. They are a function of how the system operates.

Venuti, p. 12.

Pym and Chrupała, p. 34.

Johan Heilbron, “Towards a Sociology of Translation: Book Translations as a Cultural World-System” European Journal of Social Theory 2:4 (1999):429-444. doi:10.1177/136843199002004002

For more on this kind of research, you could look at e.g. Diana Roig-Sanz and Laura Fólica, “Big translation history: data science applied to translated literature in the Spanish-speaking world, 1898–1945” Translation Spaces 10:2 (2021), p. 231 - 259, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1075/ts.21012.roi, and most recently (so recently that we also have not read it yet, but we saw that the intro provides an excellent overview of the research in the sociology of translation), Gisèle Sapiro, Qu'est-ce qu'un auteur mondial ? Le champ littéraire transnational. Paris: EHSS / Gallimard / Seuil, 2024.

Absolutely fantastic post on the global flow of translations. So informative, so thought provoking. I have so many--not so much questions as just general areas I'd like to know more about.

Lots of curiosity about the relation between patterns of translations and patterns of population (predictably). Japanese appears to have a fairly large internal literary market relative to the population of speakers (at least as compared to, e.g., Spanish) and a low proportion of translations; is there a case to be made for literary protectionism for languages that are, where translation is concerned, already peripheral?

Also curious about the relationship between being a literary exporter and a cultural exporter, e.g., South Korea has obviously become a major cultural exporter... but are its literary exports picking up as a result? Korean is the only language course at Duke to have increased enrollments in the last decade or so, so one might expect so. I understand that Turkish TV is also a major export with lots of links to the Arab world.

And about the relationship between number of translations / number volumes total: are bestsellers big enough to shift the patterns, or not?

I enjoyed it, many intriguing numbers and observations. Regarding the Russian, French and Spanish, strictly statistically speaking you cannot call them outliers - there are too few data points on the graph to authoritatively decide where is the trend and where are the outliers. I found your article because I just published a text where the 3% number gets quoted. My argument is that the 3% is the result of relative lack of interest in foreign cultures in the anglosaxon world. But that is not the only possible argument to make. Link below:

https://nomadicmind.substack.com/p/worlds-we-dont-see