We are planning to use this substack to blog about our slow-moving project Hungarian Literature in Translation. It is a quantitative project, based on the metadata of literary translations from Hungarian into any language between 1800-2009. The broad questions the data can help us answer include: What Hungarian literary works were translated, into what languages, and when? What changes, what tendencies, what patterns can we see over these 210 years? What do these patterns reveal about Hungarian literature—and, perhaps most importantly: What do the metadata of translations of Hungarian works suggest about the world system of translations?

Our project aims to analyze data about the circulation of Hungarian literature beyond its original linguistic and cultural context, and reveal the various “translationscapes” of Hungarian literature, that is: show what Hungarian literature looks like, what authors are visible and what texts are important from the perspectives of various languages. But our ambition goes beyond this. We want to know not only what works were successful, when, and where: we also want to figure out what this reveals about how literature—not just Hungarian literature, but any translated literature—circulates among languages, countries, and political systems. Hungarian is a small literature, both in terms of the sheer size of the corpus of texts and in terms of its reach: to the extent it has been published and read in places from Tokyo to Buenos Aires, from Oslo to Sidney, from Moscow to Paris, however, it passed through channels and mechanisms similar to, or identical with, the channels and mechanisms through which any literary translation circulates. One of our aims is to trace the historical evolution of the world system of literary translations.

With our project, we follow in the wake of similar quantitative research on other smaller literatures, research that also aimed to explore translation flows between languages, reveal the historical dynamics of the world system of translations, and register the shifts in the hierarchies of central and peripheral languages. Most of those earlier studies only covered the period from the late 1970s through the early 2000s.1 Even the study with the most ambitious scope only covers one century.2

Our project goes beyond such research both in terms of its chronological scope and its granularity:

Our 1800-2009 timeframe means that we take a longer view of the various translationscapes of Hungarian literature, and through those changes, discern some of the constellations that preceded the 20th-century emergence and especally the late-20th century consolidation of the contemporary, anglo-centric, neoliberal system of world literature.

And rather than merely focusing on languages, dates, and quantities (how many books were translated in any given year into any given language), we also make use of the information about authors, titles, and places of publication as we trace the world-literary shapes of Hungarian literature.

We are able to reach back all the way to 1800 because our data comes from more than one source. Like many others, we draw on UNESCO’s Index Translationum, which covers 1978-2009. We combine this dataset with the digitized version of Bibliographia Hungarica (1800-1978), compiled by Tibor Demeter and Rózsa Óvári between 1947-1978. Kiru has written a post here about where additional data could come from.

We will write more about all this: about translationscapes, about world systems analysis, about the Cold War, about Demeter and Óvári, about building the database, about the changing hierarchies of languages, and about many other things. We will need to explain for example what it is we are even counting here. (Books. But what counts as a book will require a whole separate post.) For now, just a couple of crude charts and lists, to answer some of the most basic questions someone might want to ask.

Note that the database is still a work in progress: all numbers are preliminary!

Languages

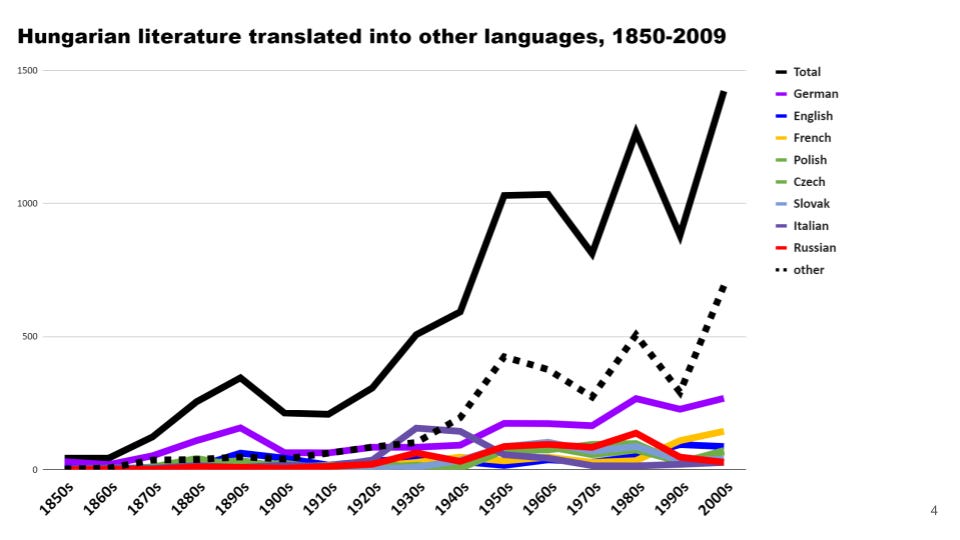

As the crudest possible summary of our data, the chart below shows the number of translations per decade, from the 1850s through the 2000s. (The number of translations in the first half of the 19th century is so low, both in absolute numbers and proportionally, that we are omitting that period from these charts. It would just be a flat line hovering in the single digits, and we need the space for the chart to be somewhat legible.) The black line shows the totals, and various colors indicate the output in each of the eight largest target languages: German, English, French, Italian, Russian, Polish, Czech, and Slovak.

The dotted black line represents translations into all other languages, some of which (Romanian, Spanish, and Serbian, for example) missed being individually represented only by a few titles. We have data about translations into 69 languages. Many of those other 61 only feature with just a few works—but the numbers add up.

If we focus on the 8 most frequent target languages, we get this image:

This chart shows a lot of fluctuation, but one thing remained remarkably stable over these two centuries, namely, the importance of German among the target languages. With the exception of only two decades, the 1930s and 40s, German was the single largest target language for translations from Hungarian. Translation into German has provided access for Hungarian literature to its largest audience, and it also facilitates translation into other languages.

The baffling expansion of Italian in the 1930s and 40s has a lot to do with several factors: the close state-sponsored cultural connections between the two countries, the tendency of the Italian publishing industry to issue relatively small print runs identified as separate editions (and therefore distinct catalog entries), the publication of novellas in cheap pamphlet form [as well as, we are adding a few weeks later, due to the active promotion of literary translation in fascist Italy.3]

More momentous changes happen during the Cold War, with the rise of Russian to second place among target languages, the increase of the number of publications in the languages of the Eastern Bloc—and the implosion of this circulation with 1989.4

And then there is English, which will soon be a subject of a separate post. Although English emerged to absolute dominance over world literary circulation over the course of the 20th century, this does not mean its rise to dominance among translations from Hungarian. The prestige of English-language translations can be very high, as English language publication means access to a larger market and also serves as a gateway to other languages. But our numbers show that German remained an essential gateway for Hungarian writing to further translations, both to regional and global audiences, through the first decade of the 21st century. By the turn of the millennium, French rose to second place behind German, increasingly fulfilling a similar gateway function. The robust support from the French state for translations into French clearly shows its effect here.

Top list: authors

Among the least interesting and also vaguest questions one can ask about our data is what they suggest about the success of individual authors. The vagueness has to do with the unit of analysis—more about this later. For now: a top list of authors!

The list must be baffling to anyone not reasonably familiar with Hungarian literature. Novels available in recent translation is of limited help. Imre Kertész, Magda Szabó, Péter Nádas are there, but the name of Jókai is a reminder of a longer history of Hungarian literature circulating in translations. (When asked who the greatest French writer was, André Gide supposedly responded: ‘Victor Hugo—hélas!’ Along the same lines: the greatest Hungarian writer? ‘Mór Jókai, alas.’ Queen Victoria apparently really liked his novels…)

We will try to look around for useable introductions to Hungarian literature, but there does not seem to be much. This History of Hungarian Literature by Lóránt Czigány stops about half a century ago. (The link takes you to a slightly updated html version of the book originally published by OUP.)

There is also the forthcoming collection Hungarian Literature as World Literature. It is to come out in Bloomsbury’s Literatures as World Literature series. We will soon post about the project which lead to that collection as well. For now, here is a link to their website.

Now back to the authors. The top list of authors published in translation in the last decade for which we have data might look somewhat more familiar:

Top list: titles

And finally: the most successful individual Hungarian titles in translations. By the nature of these things, they are almost all novels. Different types of writing circulate differently, and it is impossible to compare lyric poets with novelists. If we included all the various selections and collections of Petőfi’s lyric poems as one entry, that would be the “title” at the top of the list…

Our data also does not say anything about edition sizes, so a self-published translation of a novella, sold in 50 copies in the local bookstore, counts the same as an edition of a print run of 100,000. And those are just the most obvious issues with the data.

But people like top lists, so here it comes: the “all-time greats.”

For each item, we listed:

AUTHOR, Original Title (date of original publication, Title and date of first English translation), and the number of editions listed in our database.

The basis of the ranking is that last figure, which only includes editions published in translation outside Hungary. There will be a post about the phenomenon of (usually state-supported) domestic publication of translations for export, and what we can say about their significance. There are, however, a couple of works in this list that were only published in English in Budapest: in those cases, we included the title and date of that edition, even though it was not included in the count.

Scroll down and enjoy. And yes, The Paul Street Boys, by far. It is not particularly well served by its English translation, although there is now a new, revised, much improved version of the old translation, which unfortunately only seems to be distributed in Hungary. In several other languages, in southern Europe especially, it has been in print for a century now, assigned to generations of middle school kids. There is a nice essay by Franco Moretti—he also had to read it at school… As I vaguely remember, it tries to do a formal analysis to identify the moment when we are expected to break down into tears. It is in Signs taken for wonders, his first English-language collection, a yellow book from Verso. I will check and cite.

32 titles: 30 novels, 2 poems—these are the books written in Hungarian that have been published in at least 25 editions in various languages outside Hungary by 2009.

MOLNÁR Ferenc: A Pál utcai fiúk (1907; The Paul Street Boys, 1927) 222

JÓKAI Mór: Az arany ember (1872; Modern Midas, 1884) 75

KERTÉSZ Imre: Sorstalanság (1975; Fateless, 1992) 64

MÁRAI Sándor: A gyertyák csonkig égnek (1942; Embers, 2001) 63

MIKSZÁTH Kálmán: Szent Péter esernyője (1895; St. Peter’s Umbrella, 1900) 53

HARSÁNYI Zsolt: Magyar rapszódia: Liszt életének regénye (1935;

Hungarian melody, 1937) 52JÓKAI Mór: Fekete gyémántok (1870; Black diamonds, 1894) 40

JÓKAI Mór: Sárga rózsa (1892; The yellow rose, 1909) 37

KERTÉSZ Imre: Kaddis (1990, Kaddish for a child not born, 1997) 36

JÓKAI Mór: A kőszívű ember fiai (1869; The Baron’s sons, 1900) 33

GÁRDONYI Géza: A láthatatlan ember (1902; Slave of the Huns, 1969) 32

ILLÉS Béla: Kárpáti rapszódia (1946;

Carpathian rhapsody, 1963—Eng transl. only publd in Hungary) 30ZILAHY Lajos: Két fogoly (1921; Two prisoners, 1931) 30

HARSÁNYI Zsolt: És mégis mozog a föld (1937; The star-gazer, 1939) 30

FÜST Milán: A feleségem története (1942; The story of my wife, 1987) 29

KOSZTOLÁNYI Dezső: A véres költő (1921;

The bloody poet: a novel about Nero, 1927) 29MADÁCH Imre: Az ember tragédiája (1861;

The tragedy of Man: dramatic poem 1908) 29PETŐFI Sándor: János vitéz (1845; John the Valiant, 2004) 29

DÉRY Tibor: Niki (1956; Niki, 1958) 29

JÓKAI Mór: Szegény gazdagok (1860; The poor plutocrats, 1874) 29

SZABÓ Magda: Az őz (1959; The fawn, 1963) 28

MÓRICZ Zsigmond: Légy jó mindhalálig (1920; Be faithful unto death, 1995) 28

PASSUTH László: Esőisten siratja Mexikót (1939;

The rain god weeps for Mexico, 1948) 27ZILAHY Lajos: Halálos tavasz (1922; no English translation) 27

KÖRMENDI Ferenc: A budapesti kaland (1932; Escape to life, 1933) 26

NÁDAS Péter: Egy családregény vége (1977; The end of a family story, 1998) 26

ÖRKÉNY István: Egyperces novellák (1968; One minute stories, 1994) 26

MÁRAI Sándor: Eszter hagyatéka (1939; Esther’s inheritance, 2008) 27

MIKSZÁTH Kálmán: Különös házasság (1901;

A strange marriage, 1961—Engl transl. only publd in Hungary) 26ILLYÉS Gyula: Puszták népe (1936;

People of the puszta, 1967—Engl transl. only publd in Hungary) 26JÓKAI Mór: Az új földesúr (1862; The new landlord, 1868) 25

KOSZTOLÁNYI Dezső: Édes Anna (1926; Wonder maid, 1947; Anna Edes, 1991) 25

Heilbron, Johan. 1999. Towards a Sociology of Translation: Book Translations as a Cultural World-System. European Journal of Social Theory 2 (4):429-444; Pym, Anthony, and Grzegorz Chrupała. 2005. The quantitative analysis of translation flows in the age of an international language. In Less Translated Languages, edited by W. LM and B. A: John Benjamins Publishing Co.; Fina, Maria Elisa. 2015. Literary translation between Italian and English. Publishing trends in Italy, the UK and the USA Lingue e Linguaggi 14: 43-68.

Halevi-Wise, Yael, and Madeleine Gottesman. 2018. Hebrew Literature in the ‘World Republic of Letters’: Translation and Reception, 1918–2018. Israel Studies Review 33 (2):1–25.

Christopher Rundle, Publishing translations in fascist Italy. New York: Peter Lang, 2010.

We are currently—in November 2024—finishing on an article on this phenomenon.