This is a test post—figuring out how all this works.

I became curious about the languages of Balázs’s works while doing tedious data cleaning work for the project Kiru (Péter Király) and I have been working on: a quantitative analysis of translations of Hungarian literature, based on a dataset that aims to be complete, including translations into any target language published between 1800 and 2009. Our goal is to discern historical changes in translation flows, using the broad framework of world systems theory. More about this project in our Patterns of Translations substack soon.

For now, a post about an author whose works pose a real difficulty for a project that sets out to count the translations of literary works originally written in Hungarian.

Béla Balázs (1884-1949) is best known today for his pathbreaking work in film theory done in the 1920s.1 He also wrote poetry, plays (including what became the libretto for Béla Bartók’s opera, Bluebeard’s Castle), novels, short stories, children’s books, and fables, as well as film reviews and other journalism, collaborated on a lot of films and wrote many movie scripts (his most famous collaborations were with Leni Riefenstahl on her 1932 The Blue Light, and with Géza Radványi on the 1947 Somewhere in Europe). That his oeuvre is hard to survey is only partly due to this sheer variety in terms of genre: Balázs’s life also shaped and scattered his writing among languages and countries.

Balázs was born in Hungary in 1884. In his youth, he was the central figure of a group of Budapest intellectuals that included his close friend the philosopher Georg Lukács as well as the sociologist Karl Mannheim. After the 1919 Hungarian Soviet Republic, he became one of the itinerant Central-European communist exiles of the interwar years. He first moved to Austria, then to Germany. In 1931, he travelled to the Soviet Union, and got stuck there after Hitler came to power in Germany. During the war, he was evacuated from his small country house near Moscow to Kazakhstan. He returned to Hungary in 1945, where he died in 1949—just as he was about to accept the leadership of the German movie company DEFA and move back to Berlin.

Émigré authors often end up publishing their works in translation first, with the original in the mother tongue still in manuscript. This condition was shared by communists and liberals—many of them Jewish—exiled from central Europe between the two wars, with the “bourgeois” writers who were forced to leave eastern Europe during the Cold War. Multilingual authors can also confound readers who are looking for the ‘original’ version. Balázs’s oeuvre was fragmented by both phenomena: his repeated emigrations shaped his writings linguistically as well as politically, not to mention the loss of manuscripts the sudden moves between countries sometimes entailed. These effects were combined with a frenzied productivity that was bilingual from the beginning.

Balázs had a German mother and a Hungarian father of Jewish descent. He grew up among Lutherans, speaking both German and Hungarian. During the first two decades of the twentieth century he sought to realize his literary ambitions in Hungarian, publishing poetry, short stories, as well as drama as Béla Balázs, a pen name he adopted in his first publications. His critical and theoretical essays on the other hand were freely shifting between the two languages. His Halálesztétika (“Aesthetics of Death”), an essay that reworks Schopenhauer into a lebensphilosophische theory of art, published in Hungarian in 1907, was based on a paper Balázs presented in Georg Simmel’s Berlin seminar, in German. A decade and a half later, in Vienna, when Balázs was rehearsing the ideas of that essay in conversation, someone present interjected that they already heard this argument, presented in Simmel’s seminar by a certain Herbert Bauer.2 Balázs was born Herbert Bauer, and in the early years of the century he still used that name as his official one.

During his exile, from the 1920s on, most of Balázs’s work appeared in German or in Russian translation. (Since we are working on translations from Hungarian, we could blissfully ignore the complicated relationship between texts that only exist in these two languages.) After his return to Hungary in 1945, Hungarian editions of these works were mostly translations from German: from 1921 on, he was writing primarily in German. Still, the bibliography of Balázs’s works is full of of complications that have repeatedly confused us. Take the example of one of the fairy tales from 1921, part of his first attempt to write literary fiction in German. “The cloak of dreams” first appeared in print in a Hungarian biweekly journal in 1921. It was a translation, presumably by Balázs himself, from the text that appeared soon after, in his 1922 collection Mantel der Träume. An expanded version of that collection was published in Hungarian in 1948, including of course the same tale—in a version different from the 1921 text. The two Hungarian publications are identical sentence for sentence, but not word for word—both are in fact translations of the same German original.3

Once you learn to ignore the chronology of the publications, this is a straightforward case: external evidence tells us what is the source text and what is the translation, and the translations also remain close to their source. But the case is also an outlier: always working with some immediate publishing opportunity in mind, Balázs is known to have worked between languages, revising himself in translation, often repeatedly—his novel Unmögliche Menschen is a fascinating example of how the text developed in parallel versions.4 Sometimes a text he started drafting in Hungarian was developed into a fuller, different German version, which in turn was translated into Hungarian, or vice versa—and back again. When working towards a publication deadline, Balázs also called on the services of professional translators—whose texts he then may have kept reworking and adding to.

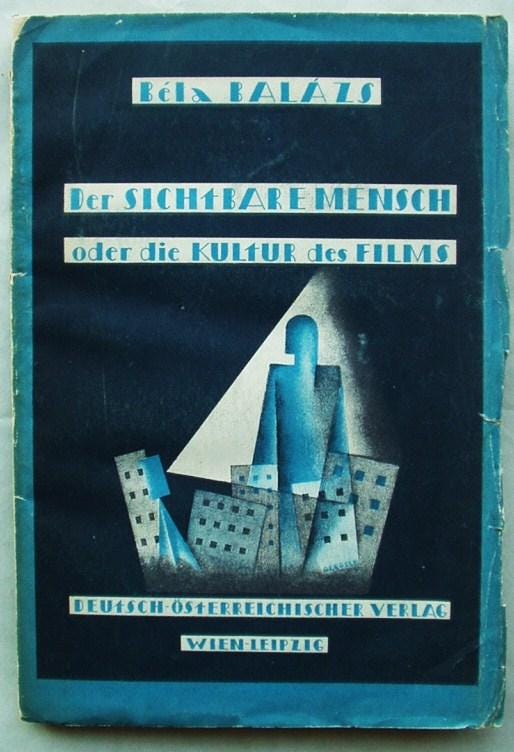

His work in film theory was first published in book form in German. These texts are also the products of the reworking and recycling characteristic of Balázs. Much of the 1924 Der sichtbare Mensch (Visible man) consists of ideas and passages that he published in German in newspaper articles. As it turns out, many of those ideas Balázs first formulated in Hungarian, in articles written for Hungarian émigré newspapers published in Vienna—which he then revised or simply translated for German-language publication.5 The process did not end there: his later works on film theory once again reworked this text, folding it into his 1948 Hungarian Filmkultúra: a film művészetfilozófiája (Film culture: the philosophy of the art of film).

His practice of writing back-and-forth between languages was further complicated by his move to the Soviet Union. Although there existed German- as well as Hungarian-language journals and even book publishing there (this is still the visionary period of a communist world literature, although it is already getting darker and scarier) the primary language of the Soviet literary public sphere was obviously Russian. Balázs worked hard to adapt to this environment, and also learnt Russian. He not only had his German-language works translated into Russian for publication, but his writing process sometimes may also have involved using that Russian translation prepared by someone else, retranslating it into German and further revising it, either because the original was lost (typescripts circulated among colleagues may or may not have been returned to the author), or because the Russian translation incorporated changes he wanted to use. And then he may also have created a Hungarian version, translating it himself, or having someone else translate it.

The play Himmlische und irdische Liebe, which became Любовь земная и небесная, which then became Irdische und Himmlische Liebe, which then became Lulu és Beáta is a good example—the second German version seemingly a translation from the Russian version made from the earlier German version, and he Hungarian version a revision based on some of the earlier versions although not in any straightforward way. Although several intermediary drafts are clearly lost, it seems pretty clear from the surviving paper trail (or rather, from Júlia Lenkei’s reconstruction of their connections) that Balázs first wrote the text in German, and the Hungarian play comes at the end of a series of translations and revisions. That versions published in the Soviet Union in Russian and German crop up in bibliographies but not in library catalogs complicates the story further. One thing that is clear from this example is the collapse of the original / translation dichotomy within the oeuvre of Balázs,6 which makes our task of sorting texts into neat boxes of “translations” and “originals” both nearly impossible and fascinating.

But there is another dimension to all this.

In his pragmatic recycling of writing across languages, Balázs seems to treat the linguistic medium as effectively transparent: as something whose only purpose is to convey an underlying idea. (The only genre that seems to escape the back-and-forth of translation is poetry—of which he writes less and less.) By refusing to worry about language and translatability, it is as if had aspired for his written work to have the same universality he claimed for the filmic medium in his theoretical work.

Balázs’s early theory of film is focused on the idea of film breaking through linguistic and textual mediation by the immediacy of visuality. In the 1924 Visible man (which I am quoting from the excellent 2010 edition by Erica Carter, translated by Rodney Livingstone), he argues that the multiplication of words through print transformed a visual culture into a conceptual one: “the word has become the principal bridge joining human beings to one another.” (10) Print is thus (paradoxically) the mechanized medium of the audible spirit. Not only are the audible and the visible alternatives to one another. As Balázs argues, the origins of language are in the expressive movements of the tongue and the lips, which were “no more than spontaneous gestures, on a par with other bodily gestures”—making sound a secondary phenomenon, a side-effect of gestures,

one subsequently exploited for practical purposes. The immediately visible spirit was then transformed into a mediated audible spirit and much was lost in the process, as in all translation. But the language of gestures is the true mother tongue of mankind. (11)

It is through film that “mankind is now busy relearning the long-forgotten language of gestures and facial expressions. This language is … the visual corollary of human souls immediately made flesh.” (10) Not only is “the culture of words … dematerialized, abstract, and over-intellectualized”--there are also “many things to say that we cannot express in words.” (11) The

new language of gestures that is emerging at present arises from our painful yearning to be human beings with our entire bodies, from top to toe and not merely in our speech. (11)

This supersession of speech also means that the filmic medium (the medium of silent cinema, that is) is “the first international language, the language of gestures and facial expressions.” (14)

For Balázs, at least in the ecstatic pages of Visible man that dream about a visual immediacy that returns humankind to a state before “the process of estrangement and alienation that started with the confusion of tongues in the Tower of Babel,” linguistic mediation is primarily an obstacle. It serves a practical purpose, not a creative or intellectual one. For Balázs, language is a secondary medium of thought, which is at home in a different medium—visuality. In his autobiographical novel about his childhood, Álmodó ifjúság / Jugend eines Träumers, he writes about the spaces and images of his memories, seeking to convey them even as he repeatedly asserts that they themselves don’t have narrative form—they precede the story he is telling, which is there to record and transmit a more fundamental medium.7 As he put it in his journals in 1916, “I don’t deduce thoughts; I see them. That is to say, I only register what is visible, what appears to me scenically.”8

It may then seem that the point of any translation, as of any writing, is to convey not an expression in another language, but something that precedes language. In fact, the utopian goal of communication is to erode the need for translation:

The variety of facial expressions and bodily gestures has drawn sharper frontiers between peoples than has any customs barrier, but these will be gradually eroded by film. And, when man finally becomes visible, he will always be able to recognize himself, despite the gulf between widely differing languages. (15)

Such a theory of communication calls for the bracketing of linguistic specificity, except in cases where that specificity is what is at stake: that is, in the case of poetry. And maybe it is also the other way round: perhaps a theory of communication that whose utopian hope is to see through language is, if not prompted, then certainly encouraged by an intellectual life between languages.

Balázs’s idea of the film script as a literary genre in its own right is relevant here. But this post is already too long.

In English, Béla Balázs, Early Film Theory: Visible Man and The Spirit of Film, translated by Rodney Livingstone, edited by Erica Carter. Berghahn Books, 2010.

Quoted from the diaries in F. Csanak Dóra: Balázs Béla hagyatéka az Akadémiai Könyvtár kézirattárában, Budapest: Magyar Tudományos Akadémia Könyvtára, 1967, p. 15.

Mese az álomköntösről (Tale about the dream cloak, in Hungarian) in Napkelet 2/24, 1921, 1454-1455. (Napkelet was a literary journal published in Cluj, Romania. Cluj/Klausenburg/Kolozsvár is the largest city in Transylvania, a historically Hungarian multilingual cultural center. It became part of Romania after World War I, but remained an important venue of Hungarian literary culture, and a place where émigrés living in western Europe including communists with no access to outlets in Hungary sometimes published their work.) The story appeared in German practically at the same time as “Mantel der Träume” (The cloak of dreams) in 1922, in a collection of his tales with the same title. (There is as English translation of the entire collection by Jack Zipes, Princeton, 2010.) The collection with some additions was then published in book form in Hungarian in 1948. It includes the same tale, in a different Hungarian version, under a title that follows the German version: Álmok köntöse (The cloak of dreams).

Júlia Lenkei: “Nagy regénytől tanmeséig: Balázs Béla, Isten tenyerén I. – Isten tenyerén II. – Lehetetlen emberek” Irodalomtörténeti Közlemények (ItK) 119 (2015): 364-386.

Károly Kókai, 'Die Frühe Filmtheorie Von Béla Balázs', Hungarian Studies, 30/2 (2016), 235-50.

Júlia Lenkei: “Égi és földi kémia” Criticai lapok 2010/1: https://www.criticailapok.hu/archivum/23-2005/37810-egi-es-foeldi-kemia and “Balázs Béla és a nyomda ördöge” Criticai Lapok 2010/2: https://www.criticailapok.hu/23-2005/37832-balazs-bela-es-a-nyomda-oerdoege

Balázs Béla, Álmodó ifjúság: regény. Budapest: Athenaeum, 1946, pp. 9, 20, 22.

Balázs Béla, Napló, vol 2 (1914-1922), Budapest: Magvető, 1982, p. 204-5, cp. F. Csanak Dóra: Balázs Béla hagyatéka, 23-24.