Early Hungarian Books: The Dark Matter

What do our data about print that survives reveal about the early Hungarian books that disappeared without a trace?

by Farkas Gábor Farkas, János Káldos, Péter Király

This post is the second part of an excursion from the blog’s main topic, Patterns of Translation. It describes another project in bibliographic data science, which attempts to offer an educated guess in response to the question: How many early modern Hungarian books have disappeared without a trace? The first part is available here.

The investigators of this project are Farkas Gábor Farkas, János Káldos, and Péter Király. The post is the written version of a presentation held as a 21st Century Curatorship Talk at the British Library on a hot summer day on 26th June, 2024.

We know of about 6000 publications printed in Hungary or in Hungarian before 1700. In a previous post, we have traced the outlines of the surviving corpus, based on the statistical analysis of a database created from the RMNY bibliography.

In this second post, we finally get to the question: can we use this statistical information to estimate how many publications we do not know anything about? Is there a way to extrapolate from what survives, and estimate the percentage of all printed publications that have disappeared without a trace?

Estimating the loss

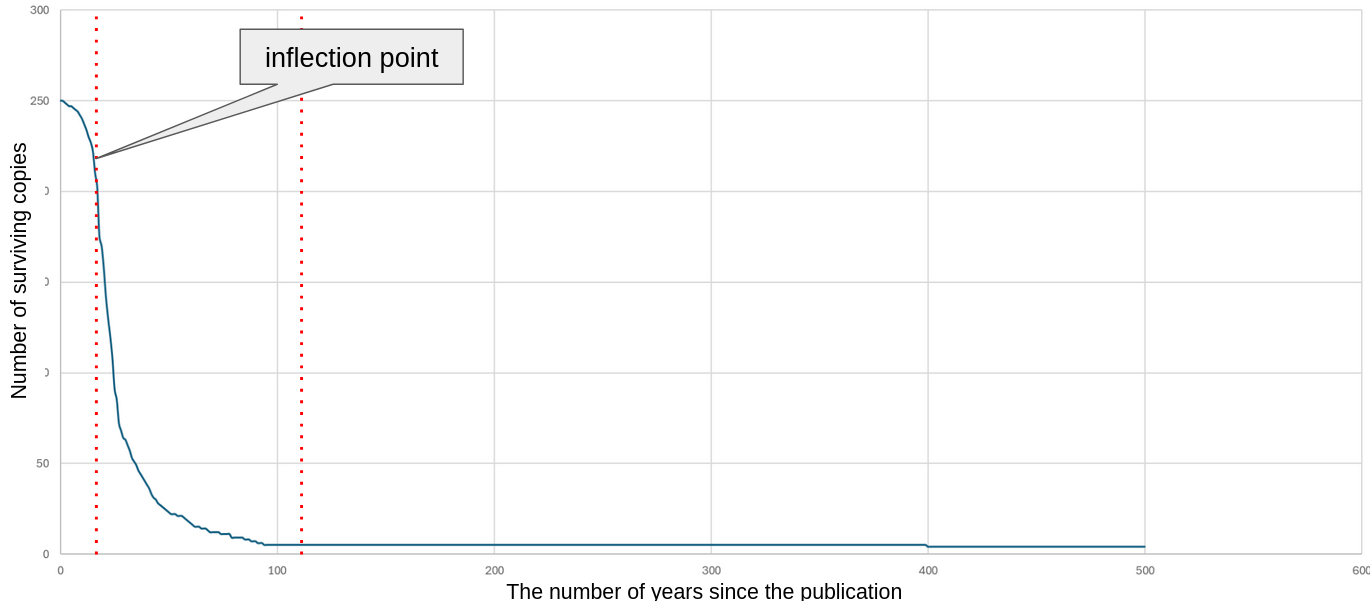

The chart shows the stages in the long-term life cycle of a publication and the factors that influence them. The life cycle of printed publications has many similarities with the life cycle of biological species. Similar terms can be used to describe the stages. The stages of 'functional functioning', 'functional extinction', 'endangerment', 'extinction' in the biological sense can be applied to printed publications. In biology, mathematical methods are often used to estimate the number of extinct species, as well as the area of species. "It is estimated that more than 99 percent of all species that once lived on Earth, some five billion species, are now extinct."

There are number of estimates that are relevant to projecting the full volume of Hungarian books in different periods. Regarding the medieval book culture of Hungary, we have the following figures:

László Mezey: 55,000 codices

Edit Madas: “a single existing document is missing dozens or even hundreds of others”

and most recently Zsófia Bartók evaluated Mezey's (mis)calculations and explored other factors that would modify the estimate

Summarizing existing research on lost books, for the loss rate of incunabula across Europe, Andrew Pettegree refers to the work of Jonathan Greene, Frank McIntyre, and Paul Needham:

Dealing with a total population of 28,767 editions published throughout Europe in the fifteenth century, they found 2,039 surviving in three copies, 3,217 in two copies, and 7,488 in one copy only. The conservative calculation based on the last two graph points offers a total of around 20,000 lost editions.1

Many of the lost titles belong to “classes of literature most susceptible to destruction: almanacs, cheap print, abcs, indulgences, printed ordinances and ballads”—which are often left out of the bibliographies.2 (RMNy includes them.)

A study of surviving French vernacular books printed before 1600 identifies 52,000 surviving editions, and projects 59,000 lost editions—the latter being a conservative estimate.3

And finally, here are some statements regarding Hungarian imprints for the 1473-1700 period:

Ferenc Hervay: “We cannot even begin to estimate the loss to our cultural history of the works that have disappeared without a trace.”

János Heltai: “one fifth of the known printing production in Hungary we are only aware of from bibliographical tradition and other inference.”

Sorting early modern Hungarian publications

We can sort the publications printed in the period into three sets, based on the extent of our knowledge about them. In 2016, Falk Eisermann wrote about “the dark matter of the Gutenberg Galaxy”—the publications lost without a trace.4 Here, we are going to extend his metaphor, and name our three sets as

Light set: publications that exist in at least one copy or fragment of a copy in the present—items in RMNY with at least one known surviving copy

Gray set: publications that have no existing copies but for which we have some knowledge based on earlier data—items in RMNY with 0 surviving copies

Dark set: publications of which we have no copies and no other knowledge, either—the size of this set can be estimated using probabilistic statistical models (range of values)

We have a number of methods to know more about the dark matter. The existence of such dark matter may be suggested by

the realization that there are uncatalogued library collections (not every surviving copy is registered yet)

the probability of the existence of a publication

textual criticism

chance findings

statistical methods

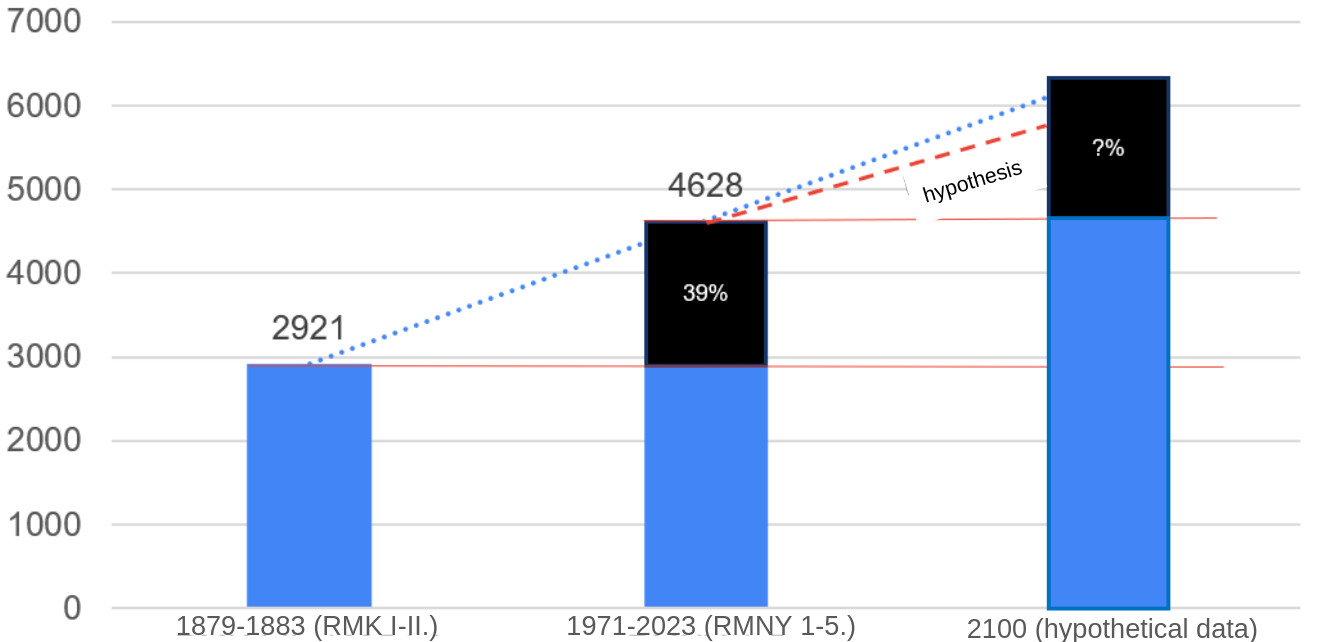

For example, extrapolating from the historical increase of the number of known titles—the expansion of the set of light matter—can be used to project the existence of more dark matter. This growth of our bibliographical knowledge can be illustrated by the Hungarian case. RMNy is not the first large bibliography on early modern Hungarian publishing. It’s most prominent predecessor is Károly Szabó’s Régi Magyar Könyvtár [Old Hungarian Library] (Budapest, 1879-) abbreviated as RMK. The first two volumes listed books printed in Hungary up to 1711.

The Introduction to the first volume of the RMNy explains why a new bibliography became necessary, describing the situation in the 1950s as follows:

… compared to what Károly Szabó published in the RMK Volumes I-II, the 16th century material had increased by 30%, the works printed in the first half of the 17th century by 40%, and the works published in the second half of the century by 50%. (vol 1. p. 19.)

Károly Szabó described only 618 early Hungarian books of the 16th century in volumes I and II of the RMK. At the moment we have 952 items for the period, which represents an increase of 54%. On the basis of the first volume of the RMNy, expert opinions estimated the number of printed works in the given period to be twice the number of works known at that time.

(The following figure is for illustrative purposes only and is not taken from the RMNYStat database.)

Our hypothesis about the future growth of our knowledge is that the increase will not be linear, as recent research has already revealed the more easily surveyed part of the 15th-17th century printed material.

Statistical approaches

The problem of the “dark matter” of the forms issued in Hungary can be illustrated using Consentius’ method, who described such a diagram in 1932: columns for how many titles survive in seven, six, five, four, three, two, or one copies, resulting in a curve that indicates how many titles survive in zero copies.5 In the chart above, the horizontal axis shows the number of copies surviving, the vertical axis denotes the number of items associated with a given number of copies. “Grey matter” represents the total number of items listed in the RMNY in 0 copies (currently 882 items). “Dark matter” indicates the number of additional (unknown) publications with a probable number of copies of 0, based on statistical methods. As a first approximation, the intersection of the curve produced by the Consentius-model with the Y-axis yields a projected sum total of the grey matter and the missing titles or dark matter.

In the literature there are number of researchers who suggested methods to estimate the survival rate. Asterisks denote those related directly to book history:

Ernst Consentius* (1932)

Ronald Fisher–Alexander Steven Corbet (1943)

Leo Egghe–Goran Proot (2007,6 20087), Quentin Burrell* (2007)

Neil Harris* (2007, 2011)

Jonathan Green–Frank McIntyre–Paul Needham (2011,8 2015,9 201610)

Mike Kestemont–Folgert Karsdorp (202011), Kestemont et al. (202212)

Alan Farmer (202313)

Jackknife algorithm

Chao1 algorithm (Anne Chao)

iChao algorithm (Anne Chao)

The distribution of the number of known copies: a total of 3479 prints, of which 1403 survive in 1 copy, 619 in 2 copies, 332 in 3 copies and 199 in 4 copies. In addition, the RMNY holds 882 forms whose existence is plausible on the basis of historical data (this is the “grey matter”).

Of course as in every statistical estimation the result is not a single number, but a probability curve. The peak of the curve is the most likely value, values to the right and below are less likely. The dashed red line indicates the borderline values, the probability of values outside this range is so low that they should not be taken into account. The range between the two is called the “confidence interval”. The estimate in this case the lower bound on the total number of possible traces. The chart could be interpreted as: “Between 1473 and 1685, probably at least 5432 territorial Hungarica have been published.”

At this stage of the research, five estimation methods were applied to the data (all these algorithms were implemented in Kestemont and Karsdorp's Python library Copia.14

For our database, the least suitable was “ace” (too narrow or estimated within too wide bounds), whereas “iChao1” seemed to be the most reliable at the moment (it includes the number of instances of 3 and 4 in its parameters, as opposed to “chao1”).

We also estimated some subsets of the catalogue:

Conclusion

Based on the statistical methods developed in the biodiversity regression (but also successfully used in other fields), we can assume that the Hungarian Gutenberg galaxy (books printed in the Hungarian Kingdom and the Principality of Transylvania excluding books printed elsewhere) between 1473 and 1685 probably consisted of at least 5432 publications, of which approximately 1071 have disappeared without a trace.

More importantly, the database underlying this research can help answer other (more mundane) research questions.

Andrew Pettegree, “The Legion of the Lost. Recovering the Lost Books of Early Modern Europe,” introduction to the conference proceedings Lost Books, Reconstructing the Print World of Pre-Industrial Europe, ed. by Flavia Bruni and Andrew Pettegree, Leiden, 2016, 1-27, at p. 6. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004311824_002

Pettegree 25.

Pettegree 5-6, citing Andrew Pettegree, Malcolm Walsby and Alexander Wilkinson FB: French Vernacular Books: Books Published in the French Vernacular before 1601 (Leiden: Brill, 2007).

Falk Eisermann: The Gutenberg Galaxy’s Dark Matter. Lost Incunabula, and Ways to Retrieve Them. In Lost Books (2016.) op. cit. pp. 29-54. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004311824_003

Ernst Consentius: “Die Typen und der Gesamtkatalog der Wiegendrucke. Eine Kritik.” Gutenberg-Jahrbuch 1932, pp. 55-110, at p. 84.

Leo Egghe – Goran Proot: “The estimation of the number of lost multi-copy documents: A new type of informetrics theory.” Journal of Informetrics 1 (2007) pp. 257–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2007.02.003

Goran Proot – Leo Egghe: “Estimating Editions on the Basis of Survivals: Printed Programmes of Jesuit Plays in the ‘Provincia Flandro-Belgica’ before 1773, with a Note on the ‘Book Historical Law’.” The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America, Vol. 102, No. 2 (June 2008), pp. 149-174. https://doi.org/10.1086/pbsa.102.2.24293733

Jonathan Green – Frank McIntyre – Paul Needham: “The Shape of Incunable Survival and Statistical Estimation of Lost Editions.” The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America, Vol. 105, No. 2 (June 2011), pp. 141-175. https://doi.org/10.1086/680773

Jonathan Green: “Databases, Book Survival, and Early Printing.” Wolfenbütteler Notizen zur Buchgeschichte, Vol. 40 (2015), pp. 35-47.

Jonathan Green – Frank McIntyre: “Lost Incunable Editions. Closing in on an Estimate.” Lost Books 2016. op. cit. pp. 55-72. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004311824_004

Mike Kestemont – Folgert Karsdorp: “Estimating the Loss of Medieval Literature with an Unseen Species Model from Ecodiversity” CHR 2020: Workshop on Computational Humanities Research, November 18–20, 2020, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. pp. 44-55. https://ceur-ws.org/Vol-2723/short10.pdf

Mike Kestemont – Folgert Karsdorp – Elisabeth de Bruijn – Matthew Driscoll – Katarzyna A. Kapitan – Pádraig Ó Macháin – Daniel Sawyer – Remco Sleiderink – Anne Chao: “Forgotten books: The application of unseen species models to the survival of culture.” Science, 2022, 375 (6582), https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abl7655

Alan B. Farmer: “Lost Books: The Dark Matter of the Early Modern English Book Trade” Carl and Lily Pforzheimer Foundation Lecture 2023.12.01 at Harry Ransom Center (University of Texas at Austin) recordings on YouTube

Mike Kestemont – Folgert Karsdorp: “copia. Bias correction for richness in abundance data.” https://github.com/mikekestemont/copia

great to read this as I’ve often asked myself similar questions about seventeenth century. I’ve speculated a bit, more about relative survival rates of different kinds of prints than absolute numbers, but haven’t made a sophisticated study or even an unsophisticated one

from an earlier period, Ferdinand Columbus, the illegitimate son of the explorer, had a collection of 3200 prints, the inventory of which survives. the collection itself is lost, but Mark McDonald made a close study of the inventory, I think he was able identify about half of the prints