by Farkas Gábor Farkas, János Káldos, Péter Király

This is another excursion from the blog’s main topic, Patterns of Translation, but not wandering too far. It describes another project in bibliographic data science, which attempts to offer an educated guess in response to the question: How many early modern Hungarian books have disappeared without a trace?

The investigators of this project are Farkas Gábor Farkas, János Káldos, and Péter Király. The post is the written version of a presentation held as a 21st Century Curatorship Talk at the British Library on a hot summer day, on 26th June, 2024.

We know of about 6000 publications printed in Hungary or in Hungarian before 1700. A new database allows us to explore the metadata of this corpus quantitatively. What does a quick look at the data reveal? And is it possible to estimate how many do we not now anything about? What percentage of all printed publications have disappeared without a trace? What is the ratio of this bibliographical dark matter to the surviving body of printed material? Any attempt to answer these latter questions will need to start with what we know, so that’s what we discuss in this first post.

I. Introduction

Our research questions are:

Is it possible to estimate the total volume of printed publications based on bibliographical data?

What methods are described in the literature?

More specifically, using available data and methodologies, can we estimate how many early Hungarian publications have disappeared without a trace?

What are the chances of survival of the works in print?

Based on the date of publication, place of publication, printing, language, size, volume or other physical or cultural-historical characteristics, how do groups of documents differ in terms of their chances of disappearance, and what might be the explanation for these differences?

More broadly, how does historical thought and research engage with the survival rate of documents and sources, and with the imagined totality of what once existed?

These questions about cultural heritage can be addressed by data science, asking and answering such questions as

What useful data sources are available?

What existing tools can we use, and what new tools do we need to create?

How can we convert a printed bibliography into a database that fits to our needs?

What would be our ideal data structure for modeling the history of early printings?

What statistics and visualizations will be useful to convey our findings?

How can the dataset be maintained?

In this first post, we look at the existing bibliographical data, explain how we turned it into a database, and using a few simple examples, we show what the database can reveal. This will serve as an introduction to our second post, where we deal with the question of dark matter: the titles that were published but have been lost without a trace.

Early modern Hungary: a very short introduction

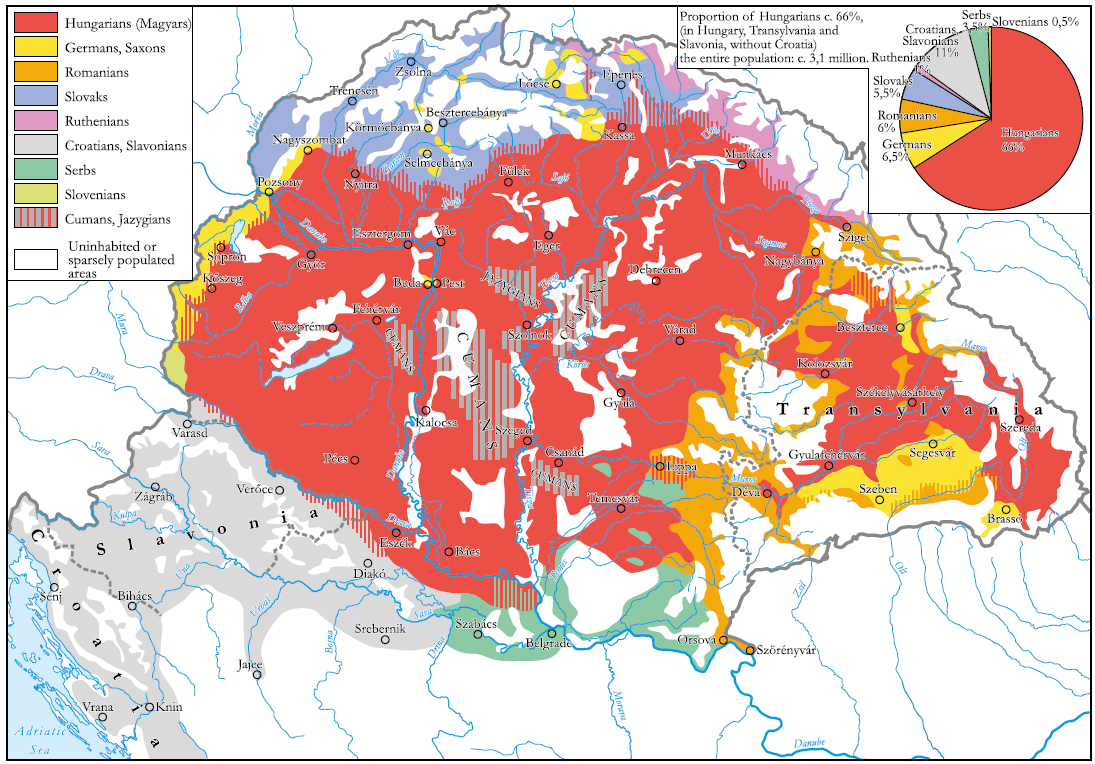

In the Middle Ages and early modern times the map of Central Europe (or East Central Europe if you like) looked different than it does today. The first map here shows the situation at the beginning of our period. By the early 16th century, the Ottoman Empire reached the southern border of the Kingdom of Hungary. To the East of Hungary, there were Ottoman vassal states, and to the West, the Holy Roman Empire, including the lands of the Habsburg family. The map changed drastically in the 1520s.

After 1526, the medieval Kingdom of Hungary was split into three parts. The Northern and Western territories retained the name of the Kingdom of Hungary within the empire of the Habsburgs. The central parts of the country came under Ottoman rule for 150 years. The former royal (Buda, Székesfehérvár) and archiepiscopal (Esztergom) seats all fell into Turkish hands. The eastern territory became a Turkish vassal state as the Principality of Transylvania.

The 16th and 17th centuries were defined by the waves of the Reformation and the counter-Reformation. After several failed medieval attempts (Pécs, Buda, Bratislava), the first university was a catholic institution, founded in 1635. [At some point we will write a post on the small, sometimes quite radically protestant colleges and the international connections they fostered—Comenius spent four years in Sárospatak in the 1650s, for example.] Political and religious divisions, as well as the slow development of higher education, all had a huge impact on book and print culture. The ethnic and linguistic plurality of the kingdom further complicates the picture.

The Hungarian majority mostly lived in the central areas of the kingdom. In the north, west, and south, they were surrounded by Slavic minorities, and in the west, also by Germans. Transylvania—the eastern third of the medieval kingdom—had a mixture of Hungarian, German and Romanian populations. In addition, most city-dwellers were German-speaking. This ethnic and linguistic complexity is reflected in the languages of print as well.

The state of research

Our research project is based on the work of the authors and editors of the series Régi Magyarországi Nyomtatványok (Early Hungarian Imprints, Budapest, 1971-). The editor-in-chief of the first volumes was Gedeon Borsa, probably the most prolific Hungarian book historian. This analytical bibliography describes a total of around 6000 titles for the target period 1473-1700, books as well as single-leaf publications, which allows for a very thorough exploration. Some of these 6000 titles are also included in other national bibliographies (Slovak, Romanian), due to changes in the political boundaries in the 20th century. The bibliography covers all the books printed in the territory of the medieval Hungarian Kingdom (including all the three early modern regions), and all books printed elsewhere that contains Hungarian texts.

Currently we are studying the period up to 1685, the time limit for the last volume that has appeared so far. The five volumes describe 4628 items (and several hundred more in the Appendices that previous studies mistakenly identified as early Hungarian prints). The material for the rest of the period is unpublished, as are the revisions (deletions, additions, changes in the information about printer, place of publications, about copies, etc.) of the items described in the previous volumes. In addition to the published series, we are also working with other data sources, that do not add any new items, but information about past or surviving copies and persons who contributed to the items (authors, printers, sponsors).

Our database

As a first step, we are creating a database of printed books (called RMNYStat after RMNY, the abbreviation of the series). Borsa's thinking was characterized by a systematic approach that is very close to that of computer science, which makes the conversion of his bibliography into a database much easier.

The conversion proceeded by the following steps:

segmentation of the bibliographic entries into data elements (such as title, author, publication place and year), following the typographical conventions

transforming them into a spreadsheet

data normalization

data structure design

The resulting RMNyStat database contains

original data from RMNy

normalized data (printing places, publishers and printers, languages)

enhanced and derived data (geo-coordinates of place names)

content characteristics

calculated values (number of sheets per publication)

print runs (we have only few data, usually based on educated guess)

We excluded ghosts, i.e. books that were included in the bibliography based on earlier information which newer research showed to be erroneous. We also excluded Hungarian books printed outside of the medieval kingdom from our the analyses, because in this phase of the research we are investigating the book production and book market within the boundaries of the medieval kingdom. For an ideal reconstruction of the Hungarian book market we would also need cover the German and Latin books printed for distribution in this market in foreign centers, especially in Vienna and Kraków, but we lack a recent analytical bibliography for these cities: the 3rd volume of Károly Szabó’s Régi Magyar Könyvtár [Old Hungarian Library] that provides this coverage was published in 1896, and is rather outdated.

The further maintenance of the database is beyond the capabilities of our small team. Such a database should be maintained by the team of the national bibliography.

II. Exploratory analysis, or: let’s discover our data!

This section highlights some of the analyses we conducted on this dataset. We use a toolbox, a variety of tools producing plots in different styles—as seen in the following images.

For the estimation we utilized Anne Chao’s R packages, and Copia, a Python package created by Kestemont and Karsdorp. We created a dashboard with R’s shiny package, Power BI and Tableau Public to create dashboards. In a later phase we will uniformize these approaches.

We have knowledge about three types of books: surviving editions that exist in different libraries (including the British Library), editions known to be lost for whose past existence we have solid bibliographic or philological evidence, and ghost editions that we excluded from the database.

In the chart above, we can see the ratio of surviving (light grey) and known lost editions (dark grey) by decades. The share of lost editions shows a slightly decreasing trend: as we get closer to our time, fewer and fewer of the books that we know to have existed are lost.

The number of publications per printing place shows a balanced distribution over space and time. There is no “central” location, such as Paris in France or Vienna in Austria. This is partly due to the fact that previous political centers (Buda, Esztergom, Székesfehérvár) were occupied by Ottomans. Several cities both in the Kingdom of Hungary and in the Principality of Transylvania established strong printing traditions, resulting in a de-centered landscape of print similar to what we see in the Low Countries and in Germany—although this landscape was produced by quite different circumstances of course.

In some locations, the printing and publishing activity was constant through most or all of the period. Some locations appear only for some years. Underlying the geographical discontinuity we often find a continuity of production: some printers wandered and settled down for a few years, and then moved on—because of war, religious changes (this is the time of the reformation and counterreformation), epidemies, changes in patronage, etc. In some cities, an established printing tradition was also interrupted, for example in Bratislava/Pozsony in 1650s and 1660s.

Based on previous research we categorized the editions into seven large types, and examined how their ratio changed over time.

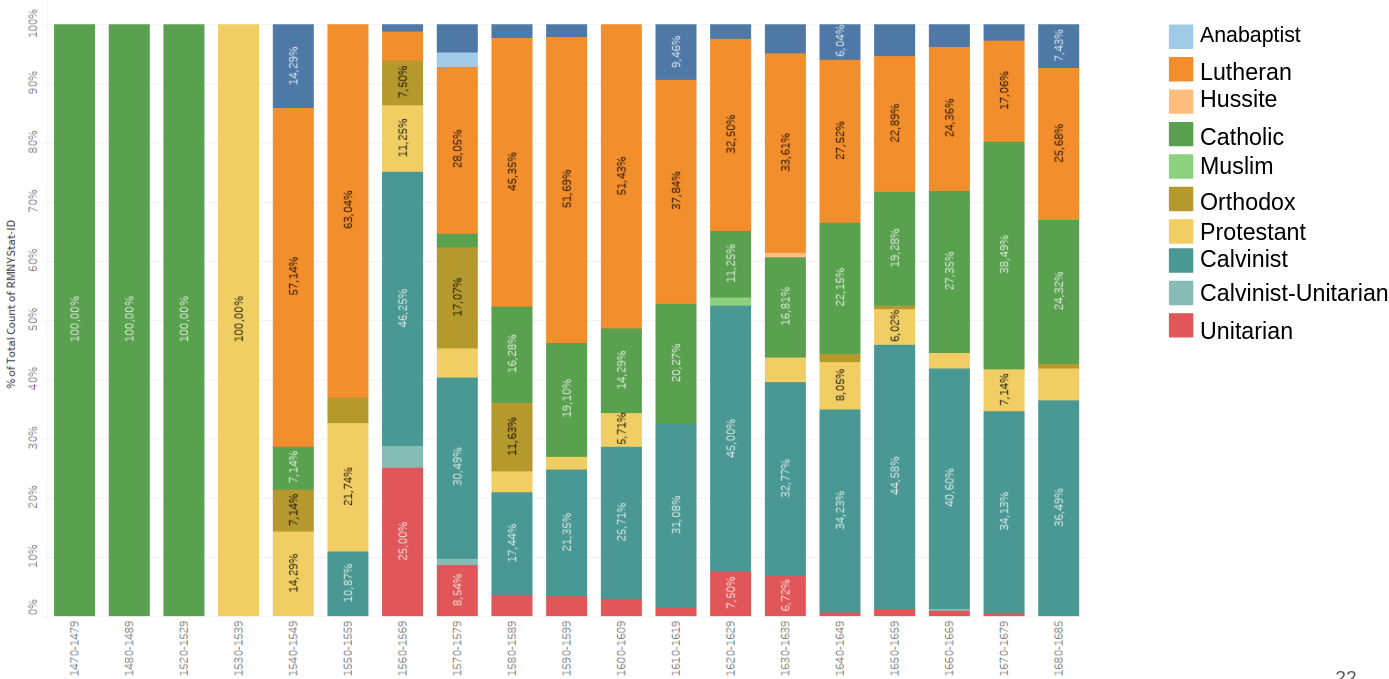

This analysis confirms the sharp decline in the publication of entertainment (including literature) from the start of the 17th century on. Parallel to this, there is a continuing increase in the number of religious publications through the rest of the century. These we can also analyze according to the denomination they represent.

Due to the Reformation, Catholic books disappeared around the middle of the 16th century, and did not become dominant again until after our period. Unitarianism (the followers of Michael Servetus) had a strong decade in the 1560s, then almost disappeared. (We used the category “protestant” to denote books we were unable to assign to a specific denomination—the boundaries among the various branches of Protestantism were not always clear.)

Our database also allows us to analyze the corpus from the perspective of the length of the publications.

The mean number of printing sheets per item was less than 50. The outlier is the first full Hungarian Bible (in 1590), which was an extraordinary performance compared to any other publication. The press belonged to an itinerant printer, the place of publication was a small village. The book has 2412 pages and weighs 6 kilograms.

Our database also includes location data: printing places, current location of known copies in collections, as well as the location of earlier collections to which a copy belonged to. We normalized and georeferenced these place names, and created some maps. Here are two of them. (Note that the maps use present-day state borders.)

In the first image we checked the ratio of the number of all editions printed at a location, and the number of known copies registered in the same place. As we can see, our database most probably under-represents the holdings of libraries in western Slovakia (no copies in Trencsén / Trenčín, Zsolna / Žilina, Nagyszombat / Trnava)—it would be worth cooperating with Slovakian librarians to collect more data.

The second map shows the locations that produced the most sheets. We would highlight here that the map is interactive: a researcher can select filters (number of printing sheets, publication year, number of locations), and the type of visualisation. Some of these images are come from an RMNYStat dashboard.

A related project

To conclude this post we are sharing two charts from Anita Markó’s doctoral dissertation: The beginnings of the literary institution in Hungary: intellectual societies in the Middle Ages and early modern times (2020, Wien–Budapest).1 Her research project is independent from ours, we did not know about each other until recently. It is based on the same data source. She worked with pre-1600 publications in the RMNy. We want to call attention her work here because she also built a database, and applied a data science method—network analysis techniques and metrics—to the data extracted from the first volume of RMNy. One of her main research questions was: how were intellectual associations constituted in the period?

She categorizes people connected to the publication according to their roles—identifying not only the printers, authors, authors as well as addressees of dedications, but also promoters, i.e. financial etc. supporters, and others—uses network analysis to find important figures: people who were either central nodes thanks to their many contributions, or functioned as nodes connecting relatively distinct parts of the network.

In the next post: what does the statistical analysis of what we know reveal about what we don’t?

Markó Anita: “Az irodalmi intézmény kezdetei Magyarországon: értelmiségi társaságok a középkorban és a kora újkorban” (Budapest-Bécs: ELTE BTK Irodalomtudományi Iskola - Bécsi Egyetem, 2020). https://doi.org/10.15476/ELTE.2020.125. The underlying database: Markó Anita: “A Régi magyarországi nyomtatványok (1473 - 1600) hálózatai: adatbázis : Markó Anita munkajegyzetei.” (Manuscript) Budapest - Bécs (2020) https://real-ms.mtak.hu/17675/