We recently posted a piece about the stunningly low, 3% share of translations of English-language book publications, and how one can make sense of this figure in a global context. We were working with the findings of previous studies. Now we take a quick look at the available data, or rather, the lack thereof, and at some ways to get more.

Although the 3% has served as a powerful slogan in the fight for more foreign literature to be published, there are still remarkably few good quantitative analyses on translation flows. And that should not be surprising. It must already be clear from our previous post that we have a problem with the data. We were talking sometimes about the US, sometimes about the UK plus Ireland, sometimes about English as a target language, even though it is clear that the US and the UK markets are not simply mirroring each other, and English-language publication also happens in other countries. We have also been vague about whether these figures refer to translations in general or to translations of literary works—not to mention what is even called “literary”: are children’s books included? what about essays? genre fiction? drama?

We have been vague or inconsistent because of the differences among the data sets used by the studies we discussed, and because there is no good way to reconcile them with each other. That is to say, we just don’t have the data to think about the problem of global translation flows from a global perspective in a nuanced way. It is nothing short of embarrassing that the numbers compiled by Lawrence Venuti—a scholar much revered, but by no means for his quantitative work—in his 1995 classic The Translator’s Invisibility are occasionally still cited, not as reminders of an early stage of research, but as information. The situation is pretty dire—but there are some promising new developments.

Before we would start, two important points.

Unless indicated otherwise, the unit of translation data is the edition—a seemingly straightforward but as it turns out not always well-defined entity.1 This squarely book-oriented approach (where the 1987 Schocken edition of the Muir translation of Kafka’s Amerika is one item, the 1997 Penguin edition of Michael Hoffmann’s translation is one item, the 2002 New Directions edition of the same translation is one item, the 2008 Schocken hardback of Mark Harman’s translation is one item, and the 2011 paperback edition of the same translation is also one item) is not the only one possible. For example, the Publishers Weekly Translation Database only includes new translations, i.e., the first American editions of English translations of works that had not been translated into English before: no new translations of works already translated, no new editions of existing translations. None of the Amerika-editions above would qualify. Different data sets tell us different things.

We should also remind you that in America, we don’t have access to data about print runs or the number of copies sold: Melanie Walsh explained the situation two years ago well, so we won’t do so again, but it is important that everyone interested in data about culture is aware of the extent to which commercial interest prevents us from accessing data about the world in which we live, and uses the same data to shape the world for us.

National publishing statistics sometimes do have information about print runs, but in the publicly available datasets scholars have worked with, a vanity publication issued in 100 copies and never actually sold in a bookshop is one item, and a paperback edition of a bestseller printed in 100,000 copies is also one item. We all wish that we knew more: but the problem is not that data humanists are not doing what they ought to be doing. The problem is that the numbers we want are corporate assets. And if we want global figures: no one has those numbers now. (Although please do tell us if we are wrong about any of this…)

So, what is the data researchers have been using?

Before online access

There were very interesting quantitative studies based on publications of national bureaus of statistics and various trade sources before online access to digital databases would have been conceivable. Manipulating the data was obviously more challenging around 1990 than it is now, but some of these bibliometrical studies have still not been surpassed in terms of their ambition and intellectual sophistication.2 A visualization toolbox does not come up with interesting questions on its own.

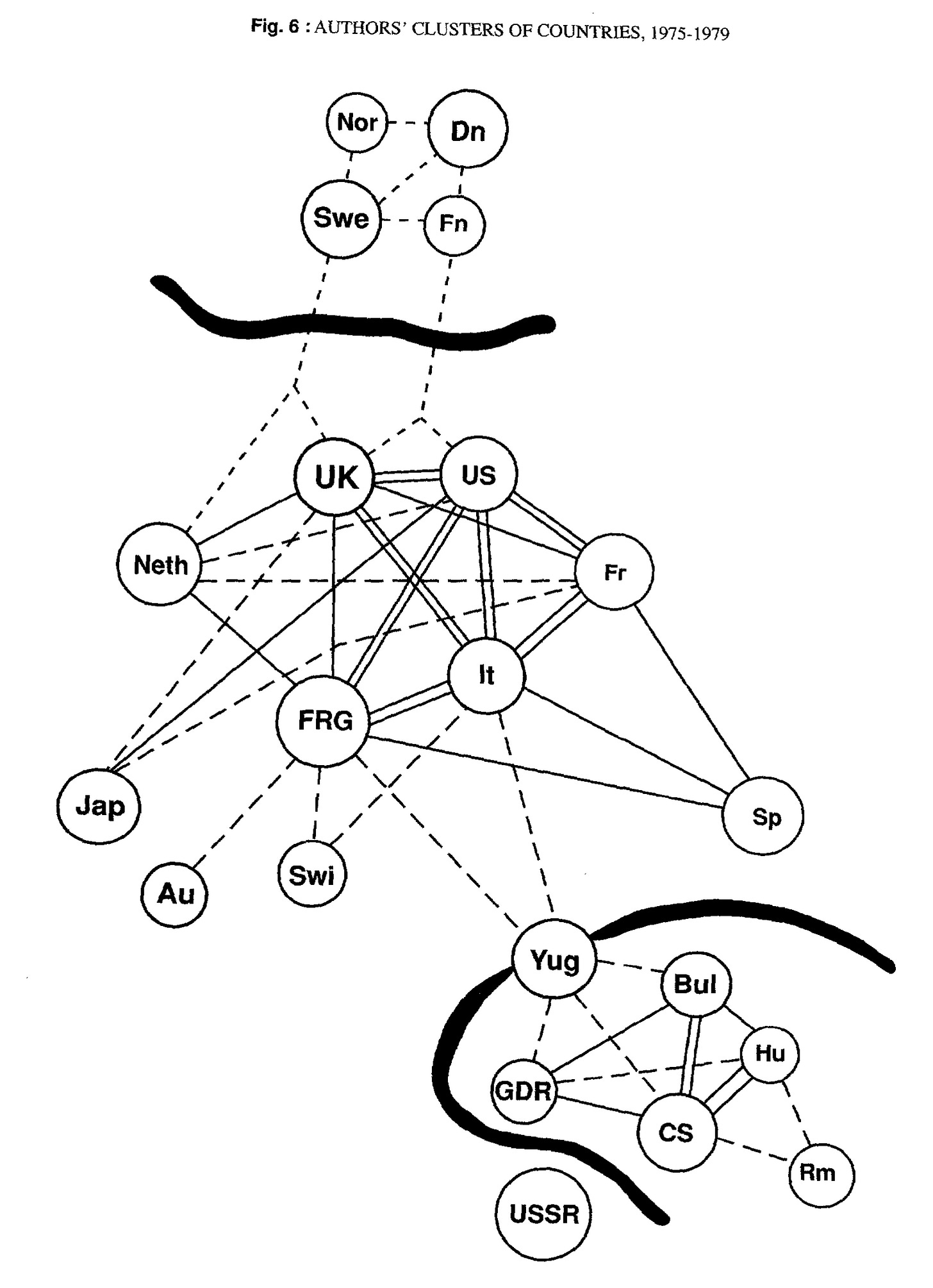

A remarkable 1992 study by the statistical and computational linguist Anatoly Yanovich Shaikevich analyzed 29 years of information drawn from UNESCO’s Index Translationum series, a print bibliography of all translated books published by UNESCO member states, a compilation of reports submitted by national agencies. Shaikevich (and his colleagues?) processed and analyzed these bibliographies for 1955-1983, and produced an account of the world system of translations during the Cold War, from the perspective of languages, authors, and large thematic categories.3 “System” here does not refer to the world systems theory approach, as exemplified by the work of Heilbron and others, discussed in our previous post. Partly because he analyzes an earlier period, partly because his analysis is more sophisticated than the Heilbron’s use of total numbers, Shaikevich’s account does not suggest a straightforward center-and-periphery model, but rather, a historically evolving network consisting of multiple clusters or communities.

The UNESCO database

Shaikevich’s study ended with 1983 because the UNESCO bibliography ceased publication after releasing data for that year. The bibliography was “computerized” starting 1979, a CD-ROM version was published in 1993, and by 2003, the database was on line. Until around 2012, the Index Translationum database (IT) promised a useful approximation of a global picture. IT can still be explored through the search interface, and datasets can even be downloaded in csv or excel—look for “Expert mode,” expertly hidden on the site, parts of which are now only accessible via the Internet Archive.

The quality of the data is not great. Differences between national standards, delays or gaps in submission, and processing problems all contribute to this. Even datasets submitted to UNESCO and supposedly added to IT were not always entered into the database in their entirety.4

In spite of these problems, there was a wave of studies coming out at the end of the 1990s and early 2000s that worked with the data from IT. Some of these we already discussed in our previous post. The 2005 Budapest Observatory report provides some basic analysis and visualizations of the data.

And then it all stopped. Information on the IT website indicates that it was maintained until around 2012. The only two countries whose data for 2011 have been processed are Monaco and Qatar. 2010 is the last year processed for 9 countries, 2009 for 29. Data for the other half of the countries represented ends before 2009. Although the website indicates that some countries continued to send bibliographic information (the last submission seems to be from Germany for 2019), for most countries, recorded submissions end around 2009-2012. There is no publicly available information about the future of the project, whether the data is still being collected somewhere behind the scenes, and what might happen to the seemingly abandoned database. When we tried to contact them a couple of years ago, they did not respond to emails. There was a long-drawn out website overhaul for UNESCO as a whole, which seems now complete, but IT did not get a new interface. Someone should just download the entire dataset before it disappears. (And post it somewhere publicly…)

The demise of the UNESCO Index Translationum database is yet another sign of the erosion of international institutions. From our present perspective, it means that quantitative research on global translation flows could only be based on data derived from the metadata service providers (Bowkers or BDM/Nielsen for English language publishing, Electre for French, etc.), from library catalogs, or from sources like WorldCat, ISBNdb, OpenLibrary, Google Books, Hathi Trust, the Internet Archive, etc. None of these sources will replace what Index Translationum promised, however spotty it actually was. The question of the public availability of the data aside, few of these offer genuinely global coverage: libraries are locally and nationally bound, whereas other other data sources, while seemingly international in their scope, source their data from the anglosphere. Books in Print claims to be international, for example, but a few quick searches can establish how random and limited its coverage is of non-anglophone book markets. (Many libraries, public and academic, provide access to Books in Print, although for some reason they tend to hide it on their website.) The big digitization projects that fed into Google Books and Hathi Trust were based at American academic libraries, which of course have lots of books from outside the US in their collections, but their coverage is nevertheless defined by their perspective…

Sources with good coverage and high quality data on the other hand tend to have a limited, well-defined scope. Quantitative research will for the foreseeable future be relying on these, and give up on the total picture. But a plurality of research projects can, through processes of triangulation, at least survey the field for which a single map based on a single source was perhaps never a real possibility.

Databases of translation metadata

The 3% database, started and maintained by Chad Post at the University of Rochester, and currently hosted by Publishers’ Weekly, was a response to the absence of publicly available information about translations published in the US.5 It contains manually collected data about new literary translations published in the US. As far as we have been able to verify its data, it is an excellent resource, and in addition to including translator info (not to be taken for granted), it also indicates the gender of both author and translator! But the principles of inclusion make this dataset hard to reconcile with data from other sources. In addition to the unique focus on first editions of new translations of works not translated before, the narrow definition of the literary—no children’s books, no memoirs, etc.—can also create a problem of compatibility. And of course this is a database of American publications.

There are several similar, sometimes very high quality translation databases, usually manually built and of limited scope. They are very useful for literary research, but of limited value for larger quantitative projects. Here is one on Turkish literature in English translation that we recently learnt about from Lisa Teichmann: https://translationattached.com/database/.

Another promising attempt on a larger scale, explicitly intended to replace IT for UK and Irish publications was launched by Literature Across Frontiers (LAF), a project currently at the Centre for Advanced Welsh and Celtic Studies, University of Wales Trinity Saint David. They published a series of useful statistical reports about translations, including the reports about translations published in the UK and Ireland that we cited in our previous posts. LAF used British National Bibliography data supplied by the British Library. Their 2012 report discusses the “data trail” from publishers through BDM/Nielsen to the BL and to LAF, and lists various other potential data sources as well. The 2012 and 2015 reports describe the work done on the raw data, and the resulting database—which to our knowledge has not been made publicly available. The partly EU-supported “Publishing translations in the UK” metadata project seems to have folded after Brexit. There have been no reports since 2017. By the look of it, a valuable dataset is sitting on someone’s old laptop in an attic.

A different approach is taken by the Digital Library and Bibliography of Literature in Translation and Adaptation (DLBT), a database maintained at the University of Vienna. It has 60,000 entries in a range of languages. Glancing at the website, we were unable to find a clear statement of its scope and how the data is sourced, but for translations with German as the target language it seems very valuable.

Between 2008-2020, CulturalTransfers.org produced several “Diversity reports” about trends in literary translations in Europe. Initially working with the IT, after 2008 they started collecting information from national publishers’ associations, and started building a database with full bibliographical data. The 2020 Diversity Report suggests that the raw data trhey are working with should be available on the CulturalTransfers.org website—which now redirects to the somewhat chaotic site Wischenbart Content & Consulting.6 We have not been able to find any data posted on the site. The 2018 and 2020 reports are offered for sale. The pdfs can also be found in various places. Another attempt that seems to have petered out. Another instance of research done with the support of public funding ending up completely privatized.

For an encouraging example of a public database that is analogous to the one we are developing, have a look at BOSLIT, the Bibliography of Scottish Literature in Translation, currently at the University of Glasgow—a bibliography that aims to represent all Scottish literary works published in translation. While the LAF project explored incoming translations, BOSLIT covers outgoing work, in many ways a more challenging task. Here, an older database was revived and re-launched in 2023 thanks to new funding.

Library data: the future?

The creation and maintenance of purpose-built databases requires special, dedicated effort—compiling information from a variety of sources. A lot of work. As an alternative, researchers can draw data from existing sources: from a national union catalog or the catalog of a national library, for example—vast, up-to-date sets of metadata that already exist. This approach poses its own difficulties: the data needs to be cleaned, filtered, and normalized for research. Most articles discussing metadata projects working with a library catalog describe these challenges. Nevertheless, catalogs are improving, as is our understanding of their intricacies as well as our ability to work with them. It seems that the next wave of quantitative research on translation flows will be relying on the catalogs of national libraries: a public infrastructure still well maintained (although struggling to keep track of the flow of digital materials and self-published stuff—but that is a problem we are unable to discuss here).

We are aware of several European initiatives and projects that use library catalogs, and a series of new or forthcoming publications indicate that there are others in the offing. This post itself is turning into a catalog already, so we are only discussing a few of these, but we would be very grateful for mentions of additional instances, whether in a direct message or in the comments on Substack.

Diana Roig-Sanz and Laura Fólica outline a study of translations in the Spanish-speaking world, working with data extracted from the Spanish National Library.7 Their essay also highlights the challenges likely encountered by any such effort, especially, the complexities of the data cleaning required. Of the biggest challenges to translation research with data from library catalogs is discovering translation data in the catalog records—see our earlier post about the challenges of MARC21 in this regard. Not all catalogs use the MARC fields the same way (sometimes they indicate that a work is translation, sometimes not; sometimes they indicate the original language, sometimes not), nor are the records of any big library internally consistent. Péter Király is currently working with one of his students on creating a computational model for establishing the probability whether a particular record in a MARC21 catalog describes a translated work.

A recent article by Jitka Zehnalová8 compares information from IT to the catalog of the National Library of the Czech Republic. Their research looks at the metadata via the IT and the Czech National Library interface, and only compares the number of occurrences of top authors, without attempting to perform more complex analyses, citing precisely the issues with the MARC21 records as an obstacle that Péter is trying to address in his current work.

Individual library catalogs can be valuable resources—combining data from several libraries can open up whole new possibilities. The European Literary Bibliography, a project of the Czech Literary Bibliography (Institute of Czech Literature, Czech Academy of Sciences, Prague) and the Polish Literary Bibliography (Institute of Literary Research, Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw and Poznan) is not translation-oriented per se. At the moment it brings together literary records form four national library catalogs and three other databases (BOSLIT being one), and it aims to include more. Most importantly, they are working on the cleaning and unification of the data, making it more readily usable in literary metadata-based research, including translation projects.9

OCLC / WorldCat already combines records from many libraries. Recently, there has been interesting work using OCLC records in translation research. The challenges of working with OCLC data are similar to working with records of individual libraries—except the quality of the records is even more variable. So research is faced with a very large volume of very messy data. Nevertheless, in an article just out, Ondřej Vimr has shown how the data can be processed and put to excellent use in research on outgoing translations from a language—in this case, to explore translations from Czech into other languages during the Cold War. (We are particularly excited by his work as its questions parallel our own.)

Research based on a single national library catalog supports research on translations into that language. Vimr’s work shows a way to work in the opposite direction, and explore translations from a language. Using a single library catalog for this purpose is not always conceivable: collecting translations published all over the world can be a logistical and even budgetary challenge. But some well-funded national libraries are also committed to collecting all such translations (most likely: all such literary translations), offering themselves as starting points for metadata research. We have already written about (warning: the post is in Hungarian…) Lisa Teichmann’s McGill PhD thesis, Mapping German fiction in translation in the German National Library catalogue (1980-2020), which shows how this can be done.10

Another attempt at developing a partial replacement for IT by creating a multi-national database seems to have been made at the University of Siegen, in Germany. Eurolit is a multi-faceted project funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft / German Research Foundation (DFG). They collect data on book translation flows within Europe, subjecting it to social network analysis. They source their data from national legal deposit libraries all over Europe—understanding Europe fairly capaciously, including non-EU countries. It is still a European project, so they won’t have answers to the American version of the 3% problem—although the place of the UK within the European translation world might provide some suggestive analogies. But there is much more to translation studies than the opportunity to ponder the annoying singularity of English. An article by Matthias Kuppler, a PhD student who collaborated on this project, is already forthcoming,11 ambitiously revisiting problems raised by the world systems research of two decades ago. Their dataset does not appear to be publicly available (yet?).

We are also exploring the possibilities of a project using catalog metadata, turning for our data to MOKKA, a Hungarian union catalog. Péter Király and his collaborators have developed a more powerful search interface for MOKKA, and we are thinking about exploring the translations we can identify among the close to 9 million records there.

Our current project is not based on a single catalog, however. There, we are working with multiple sources—using a bibliography of translations from Hungarian, the Index Translationum database, and additional data discovered during the seemingly endless data cleaning. While all the above projects have a scope of no more than a few of decades, our database encompasses 210 years. What we can discover by analyzing this data will be the subject of later posts—the first of which will describe what we can say about the role of English in global circulation, this time from the perspective of a peripheral language such as Hungarian.

This 2017 post from the Stanford Literary Lab, based on performing queries on the Bowkers Books in Print interface, for example, is incredibly vague about what the numbers even represent. It talks about “2,714,409 new books printed in English in 2015,” then mentions Nielsen data about sales figures, then proceeds to talk about the Bowkers numbers as if reflecting “book sales.” A spike in those numbers makes the author wonder whether this is about a “change in Bowkers's counting methodology” because “2009-10 seems like it would have been a bad time economically to quintuple your book printing.” Copies sold, copies printed, new titles published, new editions published, and what is even a book according to Bowker: a blur.

See fore example Valerie Ganne and Marc Minon, 'Geographies de la traduction', in Françoise Barret-Ducrocq (ed.), Traduire l'Europe (Paris: Payot, 1992), pp. 55-95.

Anatolij Ja. Šajkevič, ‘Bibliometric Analysis of Index Translationum’ Meta: journal des traducteurs / Meta: Translators' Journal 37:1 (1992) pp. 67–96, https://doi.org/10.7202/004017ar.

See the discussion of how the UK data is reflected in the IT in Jasmine Donahaye, Three percent? Publishing data and statistics on translated literature in the United Kingdom and Ireland. Literature Across Frontiers, 2012. On the quality of the IT data, see also Jitka Zehnalová, 'Digital Data for the Sociology of Translation and the History of Translation' AUC PHILOLOGICA (Acta Universitatis Carolinae Philologica) 2023:2, 55–71, discussed beow.

John O’Brien, of Dalkey Archive Press, was talking about the problem in Context magazine in the 2000s, and even put together some figures, seemingly along the lines followed by the database. On Context, see Chad Post here on Substack.

Rüdiger Wischenbart was one of the founders of the research initiative he has since folded into his consulting and analyst business, which specializes in the global publishing industry, publishing industry ranking reports and similar stuff.

Diana Roig-Sanz & Laura Fólica, ‘Big translation history: Data science applied to translated literature in the Spanish-speaking world, 1898–1945.’ Translation Spaces 10:2 (2021), pp. 231–259. https://doi.org/10.1075/ts.21012.roi

See Zehnalová 2023, cited above.

For the presentation of the project, see https://zenodo.org/records/11454445

Mapping German fiction in translation in the German National Library catalogue (1980-2020), McGill University, 2022. See our earlier brief post about this work. See also a recent article that builds on this project: Lisa Teichmann, Karolina Roman: “Bibliographic Translation Data: Invisibility, Research Challenges, Institutional and Editorial Practices” Digital Humanities Quarterly 18:3 (2024)

Kuppler, Matthias. “How Autonomous Is the Transnational Literary Field? A Network Analysis of Translation Flows in Europe.” OSF Preprints, 10 Oct. 2024.