László Krasznahorkai, world author (I.)

the system of literary translations in the 21st century

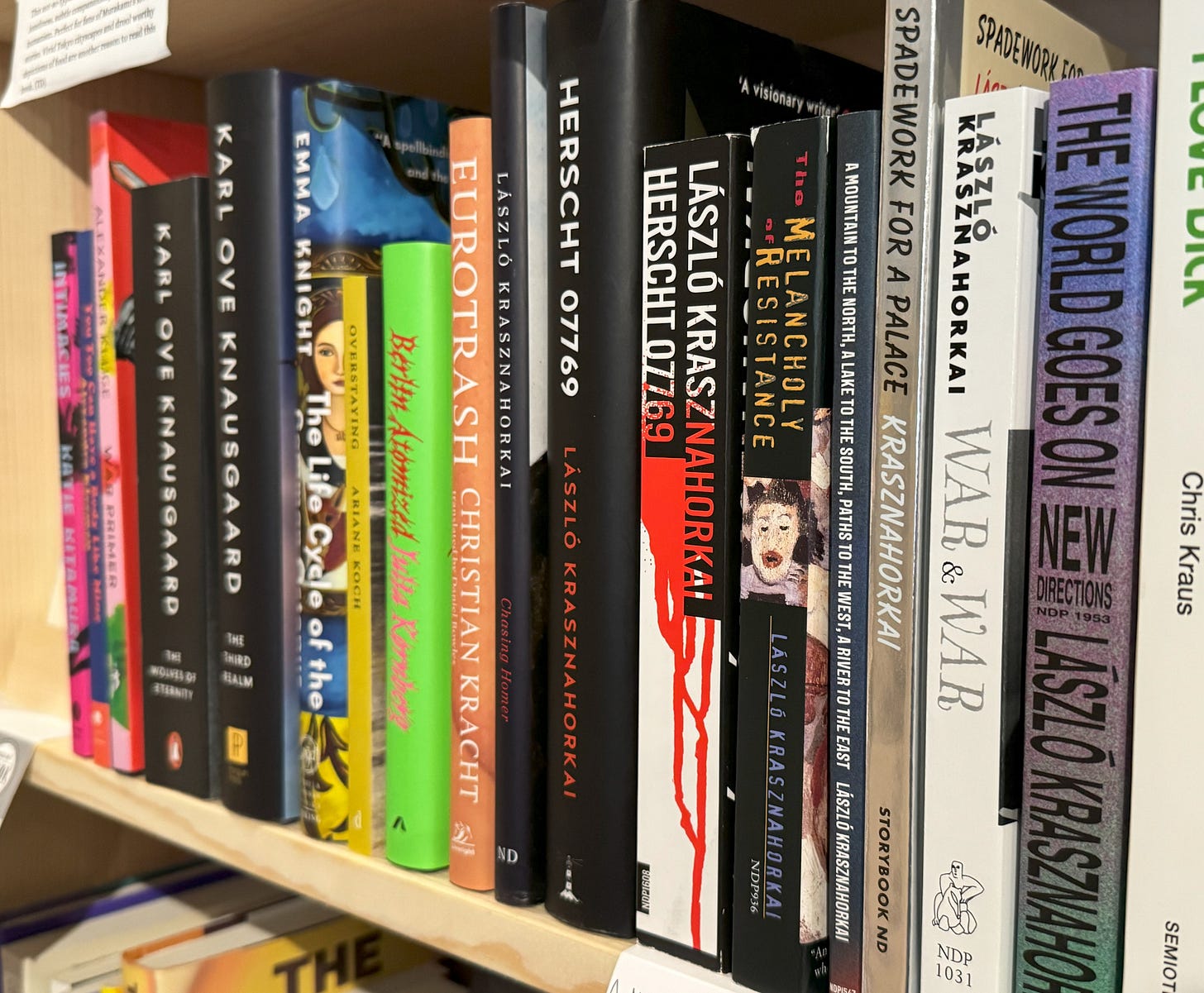

This three-part post (part 2 is here, part 3 here) originates in a conversation between Péter Király and Zsófia Júlia Szilágyi, the curator of a forthcoming exhibition (scheduled to open in June) that will celebrate the work of Krasznahorkai at the Ferenczi Múzeumi Centrum in Szentendre, Hungary. We were also motivated by the display table at East Bay Booksellers in Oakland, CA sometime late in January.

What is a world-literary author in the 21st century? How do a writer’s books circulate to make her world-literary?

In a previous post, we wrote about two Hungarian novelists, Gárdonyi and Füst, and the substantially different patterns their translations follow. Gárdonyi’s works exemplify how Eastern-European romantic nationalism became central to literary canon formation and circulation in the Soviet bloc. The translations of Füst’s novel on the other hand are paradigmatic of what we might call Atlantic world literature, propelled by the institutions and mechanisms of autonomous high-literary production. The works of Gárdonyi and Füst passed through different trajectories, reaching different audiences—and those differences effectively traced the boundaries of the two political world systems of the Cold War, and the distorted communication between them.1

This post is about the global world literary system established after the end of the Cold War. Although in many of its features a new formation, its emergence is really the post-1989 global expansion of Atlantic world literature. The translations of the works of László Krasznahorkai are as good an illustration of how this system operates as any.

A novelist from Hungary

Krasznahorkai’s first novel, Sátántangó (1985) was an instant critical success in Hungary, the book was “consecrated” by one of the most influential critics of the period, Péter Balassa, who suggested Kafka and Camus, and in terms of the prose, Faulkner, as points of orientation and comparison. Regardless what we now think of these world-literary analogies, they definitely recognized some of the book’s formal qualities as well as its sheer ambition. They also anticipate a reading which brackets (or universalizes) the cultural and socio-historical specificity of the novel’s world.

For those who have thus far managed to avoid Krasznahorkai’s books, a quick and dirty sketch. Like the books of such 1980s contemporaries as Wolfgang Hilbig or the Ian McEwan of The Cement Garden for example, Krasznahorkai’s novels grow out of the experience of the never-ending downturn that started in the 1970s: the period of economic crises and the retreat of the post-war welfare state not only in Eastern Europe but also in the Atlantic world. They convey this disillusionment not in the cynical register of economically successful metropolitan professionals (à la Martin Amis, Bret Easton Ellis, or Michel Houellebecq), but in the melancholy tones of déclassé intellectuals from the periphery, whose role is to somehow connect the dilapidated provinces to the faraway center. In imagining the illusory promise and the actual disaster brought by the center’s emissary to the periphery, and making the local crisis into a symptom of the crisis of a world system, Krasznahorkai’s novels compare interestingly with Tayeb Salih’s classic Season of Migration to the North. That promise and that disaster is the organizing trope of Krasznahorkai’s oeuvre—what Riffaterre would have called its matrix.

Krasznahorkai’s books reflect on the relentlessness of disaster—and exude a thorough skepticism about the possibility of any meaningful action other than creating a record. In this world, utopian desires only push further into abjection whoever cherishes them. The musical verve of the prose transforms a systemic social, political, and cultural crisis into a metaphysical one, as if seeking to demonstrate that “catastrophe is the natural language of reality,”2 and thus serving as a vehicle for an apocalypticism deeply satisfying to readers thus inclined. After Satantango, Krasznahorkai made high-cultural references crucial to how his characters project meaning onto the chaos—and in doing so, positions himself among the peaks of Western as well as East Asian culture, if not yet as another peak, at least as a belated mountaineer. Some might even be inclined to suggest that his work is a perfect illustration of the cultural position Lukács identified in his infamously tendentious The Eclipse of Reason as the negativity enjoyed on the terrace of Grand Hotel Abyss, where “between leisurely meals or the enjoyment of artistic productions, the daily contemplation of the precipice only enhances the pleasures of the sophisticated comfort.”

Put less sarcastically, the qualities of Krasznahorkai’s books do appear to justify Balassa’s Kafka-Camus-Faulkner genealogy. They are rife with world-literary potential. But having potential is one thing, realizing it by becoming what Gisèle Sapiro’s recent book calls un auteur mondial, a world author, another.3 For Krasznahorkai’s novels to have come to cover the display tables of independent bookstores in Brooklyn, Oakland, and Cambridge by the 2020s was a long and complex process, and the result of hard work on the part of the translators, editors, publishers—as well as by the author as a promoter of his own writing. In fact, one could argue that Krasznahorkai’s books have increasingly been defined by this work.

Below, we first look at the translation flows. We consider the factors that facilitate world-literary circulation in the second post.

Translations

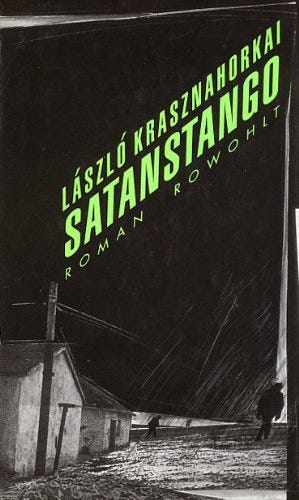

Sátántangó first appeared in German in 1990 in Hans Skirecki’s translation (Rowohlt). Publication in other languages only started after the 2000 French edition (by Joëlle Dufeuilly, published by Gallimard).

Krasznahorkai’s second novel, The Melancholy of Resistance, appeared in Hungarian in 1989, in German in 1992, and then in English in 1998, Spanish in 2001, French in 2006. The translations of the major works continue to fall into a similar pattern, starting with a relatively early German translation followed by publication in various other languages.4 German is the central language through which Krasznahorkai—and many other Hungarian writers—are first put into world-literary circulation. Other translations often clearly track the critical success of the German publication. Krasznahorkai’s world-literary success is partly enabled by his close collaboration with his German publishers. The German publication has sometimes even been coordinated with the appearance of the Hungarian original, which requires work on the translation to begin before the editing of the Hungarian book would be completed: War and War and Herscht are two substantial examples of this.

While a steady flow of German translations provided the gateway for Krasznahorkai’s global circulation, English-language success is a later phase and culmination of his world-literary trajectory. By the 2020s, Krasznahorkai has become one of the vanishingly few living world-literary authors whose works are promptly and pretty much automatically translated into English. British and American editions of his novels now appear soon after the Hungarian original, and do probably accelerate further global circulation. For this to happen took several decades, however—of the novels and other longer books, the 1985 Satantango took 17 years to come out in English, the 1989 Melancholy of Resistance 9, the 1999 War and War 17, the 2003 A Mountain to the North 19. Then things started to speed up: the 2008 Seiobo took 5 years, the 2016 Baron Wenckheim 3 years, the 2021 Herscht 07769 also 3 years.

By how many years translations are trailing the original is one way to look at the changing intensity of the English-language engagement with Krasznahorkai: another is to identify the turning point after which translations of his works, both of earlier and more recent ones, started to appear in quick succession. Although The Melancholy of Resistance appeared in English in 1998, War and War in 2006, Krasznahorkai’s English-language success and world-literary stardom really seems to have arrived with the 2012 publication of Satantango (all three novels were translated into English by the poet and translator George Szirtes). This was the moment when English translations started tracking the Hungarian publication and the German translation more closely, occasionally even coming out as the first translation, as we will discuss below.

German translations and favorable reactions in the German press were a necessary first step before other translations would happen. The quick proliferation of English-language editions that began in the early 2010s coincided with the increase in the number of translations into other languages, in what we might call a pattern of global success. Satantango appeared in Dutch and Romanian in 2012, same year as the English, bringing the total number of the novel’s translations to eight. Another 14 follow. Here, it is probably wise to remain agnostic about causes and effects: whether English translations are prompting wider circulation or are themselves just signs of a rising tide, is not immediately obvious. In the case of genre fiction, we would of course assume a strong causal link, but the translation of “high literary” material might still also be driven by factors other than sales in the largest commercial market.

But English translations of Krasznahorkai now do appear soon after the original, whereas French continues to trail German and English at a distance. French editions also started to come out in rapid succession around 2010, including some minor or less-translated books, but this never lead to a sense of urgency about having a French translation come out promptly, or indeed automatically, after the Hungarian original publication. In this sense, Krasznahorkai’s case shows the pattern of French translations idiosyncratic: not governed by what appears in English, and certainly not governing what gets published elsewhere, either. To put it differently, the French reception, while no longer the trend-setter it may once have been, still has some degree of autonomy.

Here comes a visualization of the data on which these observations are based. The limitations of the program we use means that you will probably need to blow this up a bit to see it well. On the vertical axis, we arranged the works according to the date of original publication, using English titles where a translation exists. The horizontal axis is for the date of the first publication of the translation into a given language. The translations that fall on the x = y diagonal of the graph were published in the same year as the original work.

Something about the data. We have combined information from the Index Translationum database, the Krasznahorkai bibliography of Digitális Irodalmi Akadémia (Digital Literature Academy), László Krasznahorkai's own bibliography at krasznahorkai.hu, OCLC WorldCat, as well as various national library catalogues and national bibliographies. None of these are complete.

We have written about the various data source available for such research. WorldCat for example is often misleadingly characterized as containing a record of all printed books in the world. In the case of Krasznahorkai, this is obviously not the case, especially for smaller languages (Bulgarian, Estonian, Croatian, Icelandic, etc.), and for languages whose libraries are not part of the OCLC network, but there are also gaps for larger languages that have member libraries (German, French).

WorldCat entries are often missing or have incomplete data (e.g. lacking publication date, the name of the translator, or the publisher). This makes mapping the connections among works, their translations, and their individual editions particularly difficult (WorldCat makes this available via the "View all formats and editions" option). Records written in non-Latin (Cyrillic, Greek, etc.) alphabets are often problematic. Sometimes WoldCat knows about ebook editions but not about print editions, and vice versa. While no work by Krasznahorkai is likely to exist in more than one translation into the same language, trying to distinguish among editions of different translations would also be difficult if not impossible in WorldCat. To resolve such problems, we have used library catalogues and sometimes also publishers’ catalogues—a lot of manual work to arrive at what we think is an accurate and reasonably complete representation of the book-form publications.

The simple chart above, based on our data, registers translation flows in the abstract. In our next post, we will glance at some of the specific institutional and other factors that may have helped propel the world-literary circulation of Krasznahorkai’s books, and see how they affected the patterns of translation.

The political underpinning of the contrast implies that during the Cold War, autonomy—i.e. the autonomy of the literary / aesthetic effort from political etc. determination—was itself an ideological-political performance, perceived as such on both sides of the Iron Curtain, seen as bourgeois and reactionary in the East, subsidized by the subsidiaries of the CIA in the West… That is of course putting it very crudely.

Spadework p. 68.

Gisèle Sapiro, Qu’est-ce qu’un auteur mondial? Le champ littéraire transnational. Paris: EHESS/Gallimard/Seuil, 2024.

Krasznahorkai has repeatedly said that he only ever wanted to write one book, and in the 2018 Paris Review interview he explained that he has been writing that one book over and over again, four times: Satantango, The Melancholy of Resistance, War and War, and Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming. While Herscht appears to be the fifth novel, in 2018, Krasznahorkai was very clear that Baron Wenckheim is his last. So in 2021, he suggested that Herscht is something else, closer to the “shorter” pieces, in spite of its length: what it represents is not a world, just a story. This is just one example of how strategically Krasznahorkai works on shaping his reception through his interviews, providing interpretive templates not only of individual works, but of his entire oeuvre.

Very interesting! Looking forward to part 2.

Fascinating. I'd love to read a longer piece from you that would expand on your footnote 1.