What prizes and translations reveal about writers and their books—final post about László Krasznahorkai, world author (III.)

circulation and critical success

This is the third part of what was originally meant to be a single post about Krasznahorkai. Part I looked at the translation flows, part II at the institutions and networks that propelled Krasznahorkai to world authorship. This last post speculates whether the circulation might tell us something about the works themselves.

What is a world author in the 21st century? How do a writer’s books circulate to make her world-literary? Or maybe: how does a writer need to circulate in order for his books to be world-literary? We chose the books of László Krasznahorkai to look into this question.

We have written about some of the specific mechanisms that uphold world-literary circulation. Key to the operation of this is what in a classic essay on the sociology of science Robert Merton called “the Matthew effect.” Merton invokes the teaching of Jesus that in the kingdom of Heaven, “unto every one that hath shall be given, and he shall have abundance: but from him that hath not shall be taken away even that which he hath” (Matthew 25:29) to describe the logic of the allocation of recognition and resources in the world of science, which—according to a Nobel laureate quoted by Merton—“is peculiar in this matter of how it gives credit. It tends to give the credit to already famous people.” As Merton shows, recognition, although obviously anchored in achievement, nevertheless has the structure of a self-fulfilling prophecy, not least because it can be “converted into an instrumental asset” that improves the chances of further success. “Without deliberate intent on the part of any group, the reward system thus influences the ‘class structure’ of science by providing a stratified distribution of chances, among scientists, for enlarging their role as investigators. The process provides differential access to the means of scientific production.”1

Merton’s exploration focused on the publication, reception, and influence of scientific articles. It is the sociology of science done as a sociology of reading, writing, and publication—which makes it particularly resonant with the sociology of literary circulation.

Using the crude implications of Merton’s argument: a “world author” is someone whose critical success in translation has been amplified by the prestige economy of literature to a point where the circulation of their translated works is effectively self-sustaining, at least for a period.

Recognizing an author: literary prizes

Merton was particularly interested in how prizes affect later success and recognition. With the disappearance of most regular professional critical channels, reviews at the most visited / visible venues are now little more than write-ups of promotional materials. Whether the lively critical engagement in the various Reviews of Books that have been springing up on line—including now on substack—will begin to cohere into a larger critical sphere, or whether it will remain an archipelago of voices, as some have suggested, remains to be seen. But they are unlikely to ever have the kind of influence wielded by 20th-century newspapers and magazines.

(The decline is uneven; the German press seems a remarkable holdout, for example. German-language newspapers with a wide circulation still regularly publish substantial, critical book reviews: check out Perlentaucher, the website that has provided a digest of online accessible book reviews for a quarter of a century. This may be one of the several reasons why being published in German often serves as a launch pad for further translation: it is a public sphere where there is still such a thing as mainstream critical success, which can serve as a point of orientation for publishers in other languages.)

Under these changing conditions, literary prizes have emerged as ever more important points of orientation in the global marketplace of books. Arguably, the decline of reviews as a mechanism for making and breaking literary careers coincided with the proliferation of literary prizes and their visibility as a mechanism for the production of commercial success.

Prizes convert the prestige accumulated in the literary field into sales: critical into commercial success. Even when the decision of a prize jury seems baffling or even disorienting, it will still have commercial consequences: the winner of the prize will be read in book clubs and picked up by bored commuters desperate for something to keep them off their cellphones.

While any literary prize may have some effect on the sales, the big anglophone prizes—like the Booker or the National Book Award—have an impact on the global circulation in a way German literary prizes don’t. The French prizes are somewhere in between. The Goncourt certainly registers, but it does not predict translation as surely as the Booker. The prizes of the center are themselves central.

Krasznahorkai and his translators have received their share of prizes. Without even trying to do a systematic survey: in France, Joëlle Dufeuilly received Le Prix Halpérine-Kaminsky Découverte for her translation of Tango de Satan in 2000. In the US, George Szirtes’s translation of Satantango won the Best Translated Book Award (given out by Three Percent, the enterprise at Rochester, spearheaded by Chad Post, to whom we can also thank the Translation Database, currently hosted by Publishers Weekly) in 2013. Ottilie Mulzet’s translation of Seiobo There Below got the same prize in 2014. Along with the dearly missed Paul Olchváry, who suddenly passed away last year (he translated Ferenc Barnás, for example—check out The ninth: it is short and devastating), Szirtes and Mulzet are among the most important translators of Hungarian writers into English now active. The BTBA was not something that would result in a sticker on the cover, but it certainly guided the choices of a certain audience. (The BTBA currently seems to be on hiatus.)

In 2015, Krasznahorkai won the sixth Man Booker prize. This was the last time it was awarded for the entire world-literary achievement of an author, before the prize would have become the International Booker Prize awarded for a recent book. And in 2019, back in the US, Ottilie Mulzet’s translation of Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming won the National Book Award for Translated Literature. Although in terms of visibility and commercial impact they might be lesser versions of their anglophone equivalents (perhaps a bit like Best Foreign Film at the Oscars), these are the most consequential prizes an author writing in a language other than English can hope to receive in the world’s biggest market.

The world-literary circulation of books depends heavily on the author as brand name, and also as discursive function that organizes the reading experience. Foucault associated the author function with the political and juridical constraints imposed by the state, and was eager to imagine an emergent, utopian future where it no longer mattered who was speaking. The global marketplace of books called world literature is obviously not that utopian future.

The system of prizes is an ever weakening last medium for a disappearing system of expert institutions to have a say in the creation of celebrities. Which also means that even in cases where the prize ostensibly recognizes a particular work rather than an author, the PR mechanisms of the book trade transform it into an aura that surrounds all the author’s works, not just the one that was its occasion. And in the logic of the Matthew-effect, a prize might be more important in determining the fate of the author’s next book than the quality of the manuscript.

The series of prizes Krasznahorkai has received, along with all other factors we glanced at earlier, elevated him to what we might call a “world author”—a status that pretty much condemns English-language audiences to being confronted, sooner or later, on the shelves of bookstores, with everything he has written as well as with anything he will write in the foreseeable future—regardless of the critical reception, such as there might be.

Digression about the politics of recognition

In an 2019 interview with Krasznahorkai, the remarkably eager interviewer of the Hungarian literary weekly ÉS suggests how recognition through participation in personal networks might be seen as continuous with claims upon prizes and other forms of institutional recognition:

‘Personally knowing Thomas Pynchon—that’s as much of an honor as the Nobel Prize in Literature. [?Does the interviewer mean this as a promise or as a consolation?] So how did your friendship begin?’

‘One day, he called me. I had already known his wife from before, and she must have told him how highly I regard him … We met, and our acquaintance quickly deepened into a friendship. He is a lovable, kind, and playful person. I hope that on the Thursday of the first week of every remaining October, we get to drink to the next Nobel laureate together.’2

As we learn from the Nobel website, “All of the prize announcements will be broadcast live on the official digital channels of the Nobel Prize.” So what Krasznahorkai is inviting us to imagine is a super exclusive Nobel watch party—of world authors prepared to be embittered for being passed over once again.

The lack of recognition is the one discernible organizing concern of Krasznahorkai’s reminiscences, in The Manhattan Project, about his time as a Cullmann Center fellow at NYPL, when he was tracing the footsteps of Melville and others.3 For example, Krasznahorkai visits the house in Riverdale Béla Bartók liked most of his many New York addresses, and leaves “sick at heart. One of the greatest composers of the twentieth century. And not even a marker on the house.” In case someone wanted to point out that 303 West 57th street has a plaque and even a small bronze bust of Bartók, Krasznahorkai suggests it was “some hypocrite bent on posterity” who put it up there. Recognition can only go wrong—and not being properly recognized is the true sign of greatness. Melville’s plaque in East 26th street seems “tiny” to Krasznahorkai, “small and difficult to distinguish from the texture of the wall,” and when he notices that the street was also renamed “Herman Melville Square”: “Too late, I reflected, and went down the steps of the nearest subway stop.” Nothing could make up for Melville’s “excommunication from American literature,” his being “utterly forgotten as an author” while still alive.

Krasznahorkai is intent on following in Melville’s footsteps in every possible sense, so Melville’s “excommunication” is directly reflected, on the facing page, by Krasznahorkai’s own experience of a “frosty menace of excommunication” at the NYPL. Although in practical terms, this excommunication primarily and oddly consisted in the expectation that he be regularly present at the library during his residency there, and maybe put the milk back in the fridge, it manifested most egregiously in how the Cullmann Center’s “biographical note about me failed to mention my most significant prize, namely the International Booker Prize, all they mentioned were my least significant honours.”

Krasznahorkai compares this “frosty menace of excommunication” to his experience of being raised in “a historic dictatorship, in Hungary.”

Who ever said world authorship was not deeply political.

The canon of translations

While becoming a “world author” in general and winning various awards and prizes in particular give a strong push to the circulation of a writer’s books in translation, it does not erase the differences among the individual works, or indeed the differences among their circulation. Sales figures would tell a story about their relative success, but they are generally treated as trade secrets. Translation patterns might provide some clues.

When it comes to translating world authors, the English and (especially in the case of Eastern European authors) the German language markets are big enough to be completists. Smaller markets need to be more selective. Which title is chosen by publishers to be translated into those language markets is informed by how each specific work was received in the central languages and elsewhere.

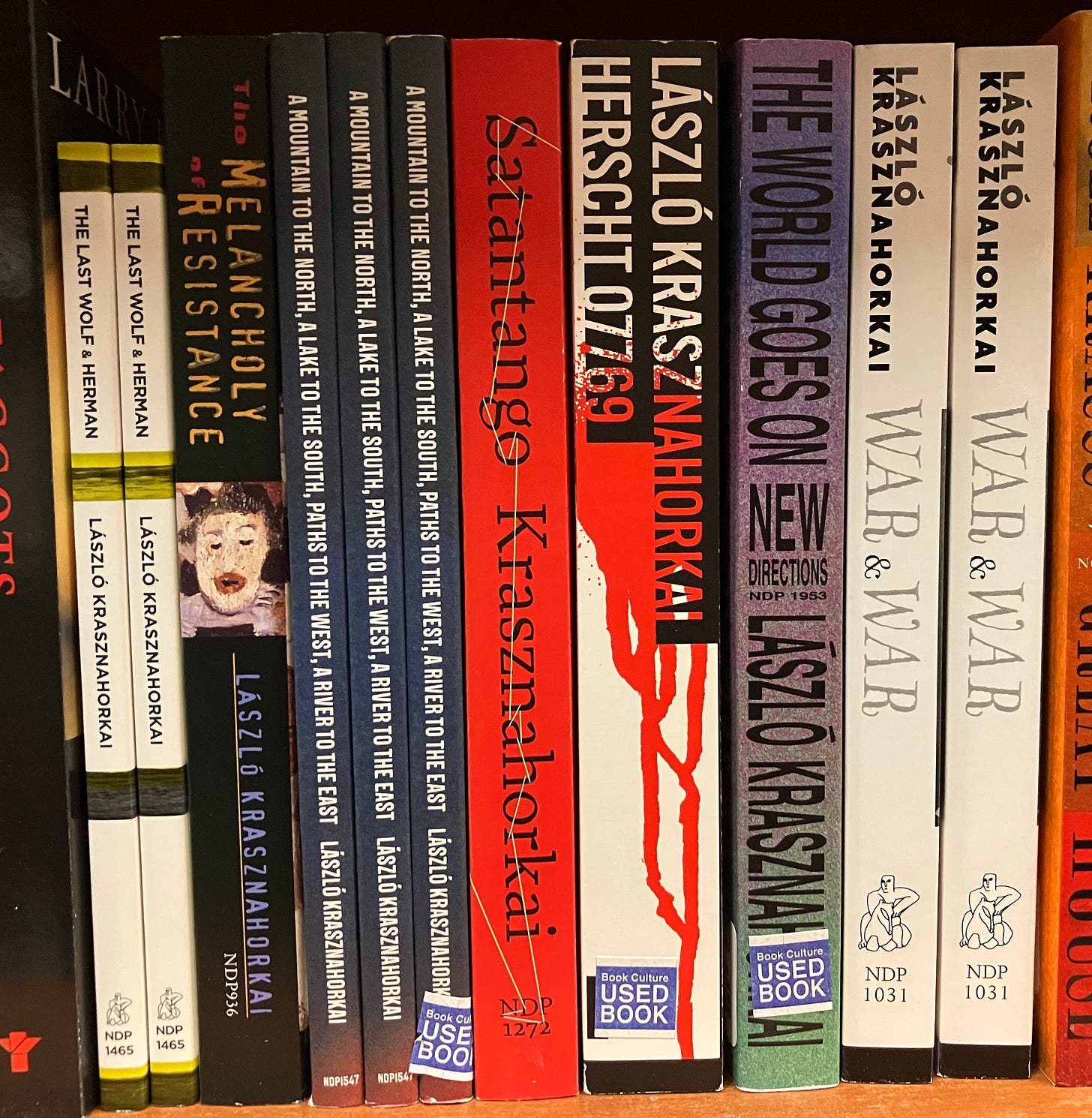

Krasznahorkai’s three most translated books are Satantango (24 languages), The Melancholy of Resistance (21 languages), and War and War (13). This could be a chronological distortion, these being the earliest works, first published in precisely this order. All else being equal, a book with more time to reach new languages will in fact reach more languages. All else is rarely equal though.

The analysis of the metadata can actually reveal something about the data—in this case, a look at differences in the circulation can tell us something about the works, or at least about how they are perceived by their audiences. If we pay attention not only to what gets translated and how often, but to the order in which an author’s titles appear in each language, we may get a more nuanced sense of the perceived importance of those titles.

Publishers read books and explore their critical reception for a living, and their choices are reflective of what they think about the appeal of the book to their audiences. In large markets, publishers can count on the power of name recognition, i.e. that the new books of a well-established world author will sell because of the name: so the fact that the most recent book by a world author is being translated does not reveal anything about the perception of the title itself. By contrast, which of the several possible titles by a world author is chosen to be the first to be translated into a new language is likely indicative of the perceived differences among their quality or canonical importance.

A publisher will want to start with a book whose success can help establish the author in a new market, sell many copies and also help sell further books by her. What is chosen to be the first title to be translated into a language is a function of how publishers perceive the potential of each title to compel a new audience.

Even after 2015, the year Krasznahorkai received the Man Booker prize, Satantango (1985) was still chosen as the first Krasznahorkai title to be translated in 7 new languages, Melancholy of Resistance (1989) in 4, War and War (1999) in 1 new language.4 Translating a recent success is a great way to introduce an author to a new audience, yet Krasznahorkai’s more recent books have only ever been translated in the wake of the success of the critically acclaimed earlier novels. In spite of the prizes they won, neither Seiobo (2008), nor Baron Wenckheim (2016) appear to have been considered as a strong enough opening salvo in any new market. They are only ever translated into languages where Satantango and / or Melancholy of Resistance and several other books are already available. Herscht is still too recent to tell if it is going to be able to revise the world-literary image of Krasznahorkai. So far, its translations have been coasting on previous success: of the 34 languages Krasznahorkai has been translated into, Herscht has only appeared in those where at least four of his other books had already been published. (To our knowledge, Krasznahorkai has not been introduced into a new language since 2020.)

The intuition about the importance of a strong opening in a new language market appears to be supported by the fact that in the two languages where A Mountain to the North was the introductory title (Japanese in 2006 and Gallego in 2014), we are aware of no further translation to have followed in the decades since.5 In the early 2000s, he travelled in East Asia and experimented with writing about the region, but as these books failed to catch on, he also seems to have bracketed them out—including, most importantly, A Mountain to the North—from retrospective discussions of his oeuvre in various interviews.

The continuous stream of new titles appears to have made little difference to publishers’ expectations about which novel on the ever growing list might be powerful enough to help establish Krasznahorkai in a new market. He remains primarily the author of his first two novels. Only after the success of those books, and only in literary markets and cultures that are big enough, have those titles been followed by others.

If anything, we have seen a consolidation and narrowing of the author’s canon as it is represented by first translations. While previously, War and War and Mountain to the North have both been chosen as introductory titles, since 2017, only Melancholy of Resistance, Satantango, and Last Wolf, which of the shorter works seems to have established itself as the go-to low-stakes first publication.

This is clearly a phenomenon of a certain inertia of the world-literary canon: these are globally successful titles, so let’s publish them in our language. But it is remarkable that no title has made enough of a splash to change this. Krasznahorkai has not been able to write anything in 35 years, since 1989, that would have shaken up the canon of his own writing.

Our point is not about the inherent qualities of the books—literary greatness is an elusive topic, and market success is certainly not among its criteria. What we are noticing is that the world-literary system in which Krasznahorkai emerged as a widely translated and celebrated contemporary author, has not yet identified any of his later books as the new masterpiece that would be able to supersede, or at least compare to, Satantango and Melancholy of Resistance. (This is not unlike how for example Louis-Ferdinand Céline, Ken Kesey, or Joseph Heller remained the authors of Journey to the end of the night, One flew over the cuckoo’s nest, and Catch-22, respectively, throughout their careers and beyond—except Krasznahorkai has two of those “only” books.) His steady rise to world authorship in the global system of translations is interestingly decoupled from how the further development, the unfolding of his oeuvre over time has been perceived by the same system. Put this differently: once you are a world author, your work will get published and translated. It will circulate. But world authorship does not guarantee the sales figures. Not even the prizes do. For the work to sell, something else also needs to happen.

Satantango and Melancholy of Resistance are also the books that were turned into movies by Béla Tarr. This may be a coincidence. Or Béla Tarr may have helped make these novels successful. Or Béla Tarr may just have a sharp sense for distinguishing stronger books from weaker ones—which is why his last movies were not adaptations of Krasznahorkai’s later books. Maybe we are dealing with some combination of the three. Or with something else. Those two are the books that deal with the moment that formed him and that he was able to imagine with diabolical clarity: the 1970s-1980s downturn as it manifested itself in Eastern Europe.

László Krasznahorkai’s most recent novel, Zsomle is waiting, came out in Hungarian in 2024.6

Robert K. Merton (1968), 'The Matthew Effect in Science', Science 159 (3810), 56-63.

Köves Gábor, “‘Beteg varázs, ezt elismerem’: beszélgetés Krasznahorkai Lászlóval” Élet és Irodalom LXIII/10 (2019. március 8.) https://www.es.hu/cikk/2019-03-08/koves-gabor/beteg-varazs-ezt-elismerem.html

The parallels between Teju Cole and László Krasznahorkai would be worth pursuing, and no better place to begin than at their books about walking New York—Open City and Spadework for a Palace. In the first installment of this post, we introduced Krasznahorkai as a writer whose works are structured by the links between center and periphery, or more precisely, are organized around characters who move between some faraway center and the periphery—think Irimiás in Sátántangó, the Prince in Melancholy, Korim in War and War, and also Wenckheim. Cole’s work is comparable in this regard, as well as for its combination of text and photography—although as a photographer himself, Cole is much better equipped to pull this off. Both have connections in both worlds, but Krasznahorkai is much better at visions of an impending disaster of the periphery, whereas Cole is unmistakably a writer of the center.

In two new languages after 2015, publishers chose a short text, the novella The Last Wolf—perhaps testing the waters with a low investment, low risk publication?

In the discussion about part 2 of this post,

suggested that we think about A Mountain to the North… in terms of world authorship. That is a great point, and it would shift or complicate our crude center-periphery account.The series of books Krasznahorkai wrote during the period after 1989 are travelogues of sorts, informed by his trips to the US, to East Asia (Mongolia, Japan, and China), as well as elsewhere—there was an aborted trip to Brazil, for example—reveal a globalizing ambition. They are records of a writer’s efforts to become familiar with, and engage with, worlds other than the Central-Europe he knows. His two travelogues (The prisoner of Urga and Destruction and Sorrow, the former not available in English) and especially the two fictional works, War and War and A Mountain to the North—are also failures: in spite of the sonorous metaphysical gestures that seek to make up for what is lacking, KL’s familiarity with the worlds he is describing in these books doesn’t seem to go any deeper than what a History Channel documentary can offer.

How both of these novelistic attempts gravitate towards touristic attractions might be a good way to illustrate this problem. In the case of War and War, from the cathedral in Cologne to a museum in Schaffhausen, and in the case of A Mountain, a 1000-year old Buddhist monastery in Kyoto—haunted by the ghost of, who else, the grandson of the Genji of The Tale of Genji, for no reason other than asserting the literary lineage by linking the book to the most famous and most translated Japanese classic. (There is also a reference to Rashomon: the gate, of course, but clearly also the story by Akutagawa, whose play with irreconcilable perspectives the book gestures at.) KL’s most successful books don’t engage in such gesturing at the targets of global tourism.

We only became aware of Zsuzsanna Varga’s informative essay about Magda Szabó’s and László Krasznahorkai’s international reputation when we were finishing this post: “The Networks of Consecration: The Journey of Magda Szabó and László Krasznahorkai’s International Reputation” Porównania 27:2 (2020) 219–233, DOI: 10.14746/por.2020.2.11. Our conclusions differ because of our system-oriented focus, but anyone looking for an overview of the reception of either of these two authors in German, French, and English, should consult Varga’s excellent article.

This was a great series. The connection to Teju Cole is interesting as well. Open City is a masterpiece, and his first book, Every Day is for the Thief is also quite good. Open City was rightly celebrated, Every Day is for the Thief I think was admired as well once people went back to it after Open City. But his recent novel, Tremor, seems to have been met with relative silence, at least after its initial publication. I was hugely disappointed, in part because Cole seemed to be writing the book he thought people wanted rather than the book he wanted to write. Perhaps he was going for "world author" status, but the book seemed rather cliched to me and not at all in keeping with his previous efforts. I'll be interested to see what he writes next.

Just one point for your data. Out of personal curiosity, I looked up Krasznahorkai in Albanian, and both The Melancholy of Resistance and Satantango have been translated. I think in the graph in a previous post it was indicated only one novel had been translated.

Thanks for that. (The "Digression," by the way, is especially entertaining, full of pathos in its depiction of your author.) A couple of comments on method in regard to your two metrics, awards and translations.

You're noting or valuing awards mainly by their effect on sales, not by their politics or their clarity of purpose (for example you're not talking about the Goldsmiths Prize). But in the absence of sales figures that can be tied to specific awards, you're necessarily using press coverage and advertising prominence as proxies -- and in that case, it's a question of which news outlets and advertising are being noted. I'm sympathetic to the problems of research here, especially because they include literary and aesthetic criteria (noticing awards that notice literary fiction), financial criteria (sales figures), and what Dan Sinykin calls "Big Fiction" issues (publishers, publicity budgets, the effect of conglomertes).

Regarding your second metric, translation. When you say "Krasznahorkai has not been introduced into a new language since 2020" the phrase implies that his books are being introduced to everyone who reads in that language—but it's not necessarily the case that readers in a given language who are interested in literary fiction will find a title just because it's been translated; and there are the further problems of measuring large and small languages, adjusting for the size of the press that does the translation relative to the country's population, and estimating the relevant percentage of the population who are engaged with fiction.

All this is to say that you might consider starting from the other side: an essay on what you read, what you subscribe to, what publishers you note, what awards you like, what countries you live in, what languages you speak -- all to put these meditations, which can be very informative, into a context.